The Role of the Yen in the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis erupted with a suddenness that stunned global markets, beginning with the collapse of the Thai baht and spreading like wildfire across the continent. While attention often focuses on the “Tiger Economies” that fell victim to the contagion, the role of Asia’s largest economy, Japan, is a critical and often misunderstood part of the story. The performance of the Japanese yen 1997 Asian crisis was not one of stability; instead, Japan’s own internal economic struggles and currency movements acted as an unwilling catalyst, both setting the stage for the crisis and deepening its impact.

Far from being a bystander, Japan’s pre-existing economic malaise—a “lost decade” of stagnation—and its policy decisions directly influenced its neighbors. The yen’s significant depreciation against the US dollar in the years leading up to 1997, coupled with a fragile domestic banking system, created a perfect storm. This article explores how Japan’s internal weaknesses and the yen’s slide contributed to one of the most severe historical currency crises of the 20th century.

The Backdrop: Japan’s “Lost Decade” and Economic Stagnation

To understand Japan’s role in 1997, one must first look at its domestic situation throughout the preceding years. The spectacular collapse of Japan’s economic bubble burst in the early 1990s plunged the country into a period of prolonged economic stagnation that would later be dubbed the “lost decade japan economy.” This era was defined by a toxic mix of low growth, persistent deflation, and severe weaknesses in the banking sector.

From 1992 to 1995, Japan’s GDP growth languished below 1.5%. A brief, fragile recovery appeared in 1996 with 3.5% growth, but this was largely an artificial bump driven by consumer spending in anticipation of a planned tax increase. The underlying economic fundamentals remained dangerously weak, setting the stage for a disastrous policy misstep.

The Ill-Timed Consumption Tax Hike of April 1997

Just as the regional financial system was beginning to show signs of stress, Japan’s government made a critical error. In April 1997, it implemented a series of fiscal austerity measures:

- The consumption tax was raised from 3% to 5%.

- Temporary income tax cuts were repealed.

- Social security premiums were increased.

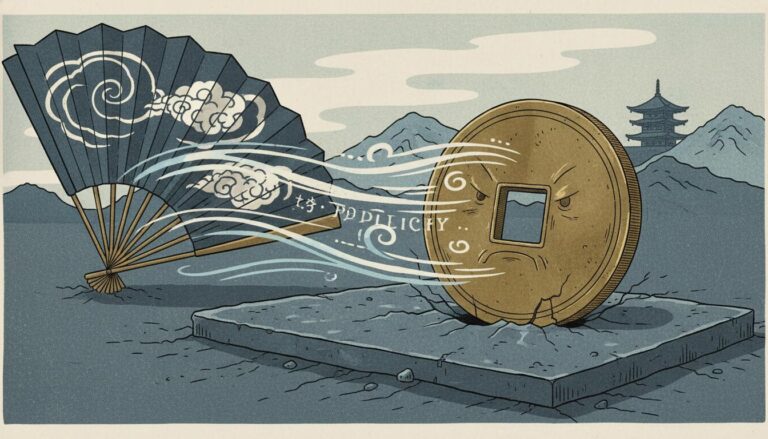

The timing could not have been worse. The result was an immediate and sharp collapse in consumer spending, from which the economy did not quickly recover. This policy decision single-handedly reversed the nascent rebound and plunged Japan back into a steep economic downturn, crippling its ability to act as a stabilizing force in the region.

The Depreciating Yen and the Japanese Yen 1997 Asian Crisis

While Japan’s domestic economy faltered, its currency was on a trajectory that directly impacted its trading partners. The yen exchange rate 1997 crisis dynamics began years earlier, creating vulnerabilities across Asia.

The Yen’s Sharp Decline (1995-1997)

The Japanese yen weakened dramatically in the two years leading up to the crisis. After reaching a peak of approximately 80 yen per US dollar in April 1995, it depreciated steadily, falling to around 125 yen per dollar by June 1997. This massive swing was not arbitrary; it was a direct reflection of Japan’s deteriorating economic fundamentals, including:

- Falling asset prices (land and stocks).

- Widespread distress in the banking sector.

- Persistently low interest rates.

- Overall weak economic growth.

How a Weaker Yen Fueled the Contagion

The yen’s depreciation had a profound destabilizing effect on neighboring Asian economies. Many of these countries, such as Thailand and South Korea, had currencies pegged directly or indirectly to the US dollar. As the yen weakened against the dollar, Japanese exports became significantly cheaper and more competitive on the global market.

This created a severe competitive disadvantage for other Asian nations. Their exports became relatively more expensive, causing their trade balances to worsen and their current account deficits to grow. This increasing vulnerability made their fixed exchange rate systems prime targets for speculative attacks, ultimately contributing to the trigger of the crisis, starting with the devaluation of the Thai baht.

Japan’s Banking Crisis Spreads Financial Pain

Japan’s financial sector was the other key channel through which its domestic problems were transmitted to the rest of Asia. Decades of poor oversight and the aftermath of the bubble’s burst left Japanese banks in a precarious position.

A Mountain of Non-Performing Loans

Japanese banks were plagued by a massive volume of non-performing loans (NPLs), largely stemming from collapsed land and stock prices. The institutional and legal frameworks for resolving insolvent financial institutions were woefully inadequate, allowing these problems to fester and destabilize the entire system. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), this protracted financial sector distress eroded both domestic and international confidence.

A Sudden Credit Crunch Across Asia

Facing mounting bad debt and pressure to meet international BIS capital adequacy requirements, Japanese banks began to aggressively reduce their overseas lending. This retreat had a devastating impact on the rest of Asia, which had come to rely on Japanese capital.

Between June and the end of 1997, Japanese bank lending to Asia fell by nearly 10%, down to $244.7 billion. This sharp contraction of credit exacerbated the financial crunch across the region, deepening the recession and turning a currency crisis into a full-blown economic catastrophe. A lesser-known but crucial fact is that for every one yen depreciation against the dollar, Japanese banks’ overseas lending capacity was reduced by roughly 500 billion yen, creating a vicious cycle.

High-Profile Failures Shake Confidence

The fragility of Japan’s financial system became terrifyingly clear in November 1997 with the failure of several major institutions, including Sanyo Securities, Hokkaido Takushoku Bank, and Yamaichi Securities. These collapses sent shockwaves through the global financial system, confirming fears that Japan’s problems were systemic and far from being resolved.

Yen vs. Asian Currencies 1997: A Regional Comparison

During the crisis, the behavior of the Japanese yen stood in contrast to other regional currencies, though not in a way that offered stability. While the yen depreciated steadily, other currencies experienced a freefall. The 1997 Asian financial crisis saw catastrophic devaluations of:

- The Thai baht

- The Indonesian rupiah

- The Korean won

- The Philippine peso

- The Malaysian ringgit

In stark contrast, China’s yuan remained stable throughout the turmoil. Backed by strong economic fundamentals and tight capital controls, China’s stability enhanced its economic standing and credibility relative to Japan. While Japan struggled with its own crisis, China emerged as a pillar of regional strength.

Ineffective Responses and Lasting Scars

As the crisis deepened, Japan found itself in a policy trap, unable to deploy conventional tools to combat its recession or help stabilize the region.

Japan’s Limited Policy Options

Standard macroeconomic responses proved ineffective for several reasons:

- Monetary Policy: Interest rates were already near zero by 1997, leaving the Bank of Japan with little room to stimulate the economy further.

- Fiscal Policy: The need to stabilize its own fragile financial system and concerns about pressure on the yen limited the government’s ability to roll out large-scale fiscal stimulus.

- Exchange Rate Policy: Allowing the yen to depreciate further was not a viable option, as it risked provoking a new round of competitive devaluations among its neighbors and delaying the entire region’s recovery.

This policy paralysis meant that Japan, instead of acting as a regional savior, was caught in the same storm, with its own economic woes reinforcing the turmoil in neighboring countries.

The Legacy of the Crisis

The 1997 crisis left deep and lasting scars on Japan and the entire Asian continent. For Japan, its struggles during this period reinforced its own “lost decade,” delaying recovery and highlighting critical failures in its economic and regulatory management. The long and storied history of the Japanese yen entered one of its most challenging chapters.

The experience offered painful but important lessons about the dangers of ill-timed tax hikes during fragile recoveries and the absolute necessity of robust financial supervision and legal frameworks for resolving bank failures.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did the depreciation of the Japanese yen contribute to the Asian financial crisis?

The yen’s decline from a high of 80 to 125 per US dollar between 1995 and 1997 made Japanese exports much more competitive. This weakened the trade balances of other Asian economies whose currencies were pegged to the dollar, increasing their vulnerability to the speculative attacks that triggered the crisis.

What role did Japan’s banking sector play in the 1997 Asian crisis?

Crippled by bad debts from their own economic bubble, Japanese banks sharply cut lending to the rest of Asia to meet capital adequacy requirements. This credit crunch exacerbated the regional recession and deepened the financial instability.

What was the impact of Japan’s consumption tax increase in 1997?

The decision to raise the consumption tax from 3% to 5% in April 1997 caused an abrupt drop in consumer spending and investment. This tipped Japan’s fragile economy back into recession, undermining its ability to act as a stabilizing force in the region.

How did the yen’s movement differ from other Asian currencies during the crisis?

While the yen depreciated significantly in the years leading up to the crisis, currencies like the Thai baht, Korean won, and Indonesian rupiah experienced a much sharper collapse during the crisis itself. In contrast, the Chinese yuan remained stable, which enhanced China’s economic influence in the region.

Conclusion: An Unwilling Catalyst in a Regional Storm

The story of the Japanese yen 1997 Asian crisis is a compelling illustration of regional economic interdependence. Japan did not cause the crisis, but its internal economic sickness—a legacy of its burst asset bubble, a paralyzed banking sector, and a critical policy misstep—created an environment where contagion could thrive. The weakening yen and the retreat of Japanese capital were powerful forces that intensified the turmoil, prolonged the pain, and reinforced Japan’s own lost decade.

The events of 1997 serve as a powerful reminder of how domestic policy and financial health can have profound international consequences. The lessons learned from Japan’s struggles continue to inform our understanding of financial regulation, macroeconomic management, and the complex dynamics of historical currency crises.