The History of Parity: Fixed vs. Floating Exchange Rates

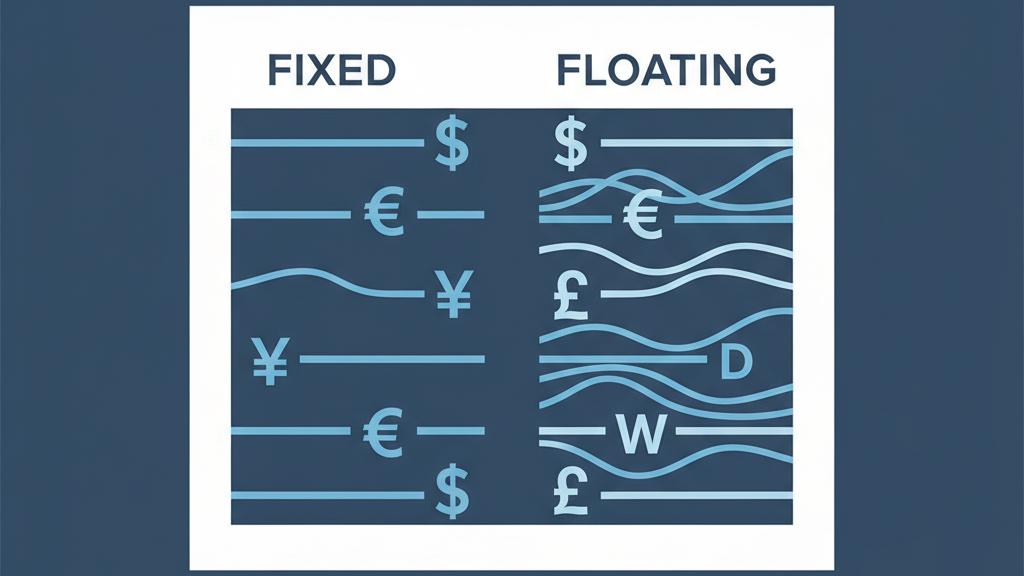

For centuries, nations have grappled with a fundamental economic question: should a currency’s value be anchored and stable, or should it be free to fluctuate with market forces? The fixed vs floating exchange rates history is a story of global power shifts, economic theories put to the test, and the constant search for a system that fosters both growth and stability. This choice between control and flexibility has defined international trade and monetary policy for over a century.

At its core, a fixed exchange rate, or pegged rate, is when a government or central bank locks its currency’s value to an external reference, such as another currency or gold. In contrast, a floating exchange rate is determined by the private market through supply and demand. Understanding the evolution from a world dominated by fixed rates to today’s more flexible system reveals the core tensions in the global economy.

The Golden Age of Stability: The Bretton Woods Fixed Exchange System

Following the economic turmoil of the Great Depression and World War II, global leaders sought to create a new international monetary system that would prevent such widespread instability from happening again. The result was the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement, which established the most extensive fixed exchange rate regime in modern history.

The system was elegantly simple in its design but massive in its scale. At its center was the U.S. dollar, the only currency directly convertible to gold at a fixed price of $35 per ounce. All other participating nations then pegged their currencies to the U.S. dollar, creating a global web of predictable and stable exchange rates.

How the Bretton Woods System Worked

This structure created two types of pegs that anchored the global economy:

- Direct Pegs: The U.S. dollar was directly pegged to gold.

- Indirect Pegs: Other currencies, like the British pound, French franc, and German Deutsche Mark, were pegged to the U.S. dollar.

For nearly three decades, this system provided a stable environment for international trade and investment to flourish. It reduced transaction costs and currency risk, helping to rebuild a war-torn world. During the height of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange era, an estimated 70% of global GDP was under these pegged arrangements. You can learn more about the intricate details of the Bretton Woods system’s history and eventual demise in our detailed guide.

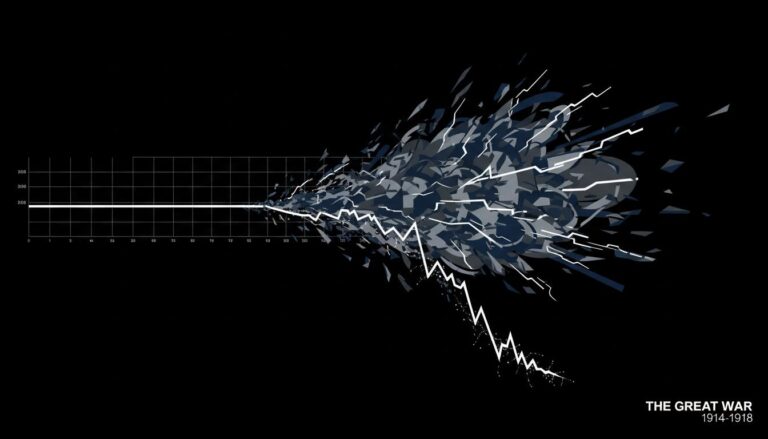

The End of an Era: The ‘Nixon Shock’ and the Collapse of Fixed Rates

By the late 1960s, the Bretton Woods system began to show signs of strain. The United States was running significant trade deficits, partly due to the costs of the Vietnam War and expanded domestic social programs. This meant a flood of U.S. dollars was accumulating in foreign central banks.

As the number of dollars abroad grew, confidence that the U.S. had enough gold to back them all began to wane. On August 15, 1971, in a move that became known as the “Nixon Shock,” President Richard Nixon formally suspended the dollar’s convertibility into gold. As described by the Federal Reserve’s own history archive, this unilateral action effectively severed the anchor of the Bretton Woods system.

The anchor’s removal sent shockwaves through the global financial system. Between 1971 and 1973, the world’s major currencies—including the dollar, yen, and Deutsche Mark—transitioned away from their pegs and began to float freely against one another, marking a pivotal moment in the fixed vs floating exchange rates history.

A New Paradigm: The History of Floating Currencies

The move to a floating rate system was initially seen as a temporary measure, but it quickly became the new norm for the world’s largest economies. By the late 1970s and 1980s, the global trend had decisively shifted toward flexible and managed floating regimes. Today, major currencies like the U.S. dollar, the euro, the Japanese yen, and the British pound all operate on a floating basis.

The primary motivation for this shift was the pursuit of monetary policy independence. Under a fixed system, a country’s central bank must prioritize maintaining the peg, often at the expense of domestic goals like controlling inflation or unemployment. Floating rates free a central bank to use interest rates and other tools to manage its own economy.

Advantages of Floating Exchange Rates:

- Monetary Autonomy: Central banks can set policy to address domestic economic conditions.

- Shock Absorption: A floating currency can automatically adjust to external economic shocks, such as a sudden change in commodity prices.

- Discourages Speculation: A free-floating currency makes it harder for speculators to mount a successful attack against a fixed peg, which can lead to major historical currency crises.

Understanding Lasting Pegs and the Middle Ground

Despite the dominance of floating rates among major economies, the story isn’t one-sided. Today, roughly 33% of global GDP still operates under pegged arrangements. These systems fall into two main categories: strict pegs and more flexible “managed” systems.

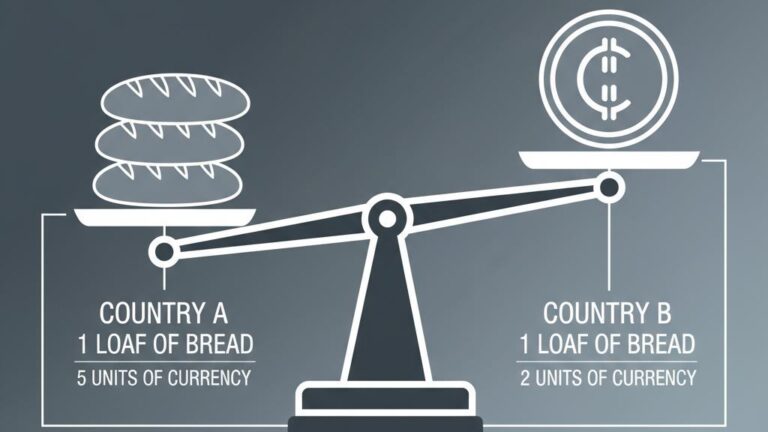

Currency Pegging Explained in Today’s World

A currency peg is a commitment by a government to maintain its currency’s value at a fixed rate relative to another currency or a basket of currencies. This requires constant vigilance and intervention.

To defend the peg, a central bank must buy or sell its own currency in the foreign exchange market. For example, if its currency is weakening below the target rate, the bank will sell its foreign reserves (e.g., U.S. dollars) to buy back its own currency, shoring up its value.

Notable examples of long-standing pegs include:

- The Hong Kong Dollar (HKD): Pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1983.

- The CFA Franc: A currency used by 14 African nations, pegged to the euro (and previously the French franc) since 1994.

As the International Monetary Fund (IMF) explains, countries choose pegs to reduce transaction costs, foster trade, and provide a credible anchor for monetary policy, which is especially helpful for smaller, trade-dependent economies.

The Rise of the Managed Float Exchange Rate

Many countries opt for a hybrid system known as a managed float exchange rate, or “dirty float.” In this regime, the currency is technically allowed to float freely, but the central bank intervenes sporadically to influence its value. The goal is not to maintain a specific peg but to smooth out excessive volatility or guide the currency toward a desired level.

This approach offers a compromise: it provides more flexibility than a hard peg while still allowing authorities to step in to prevent destabilizing market swings. It has become a popular choice for many emerging market economies.

The Ongoing Debate: How Flexible Is the World, Really?

While official declarations suggest a world that has largely embraced floating rates, some economic research presents a more nuanced picture. Experts like Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff argue that a significant gap exists between what countries say they do (de jure policies) and what they actually do (de facto policies).

Their research suggests that many countries claiming to have a floating currency intervene in the market far more than they admit, effectively operating a managed float or a soft peg. This “fear of floating” stems from a desire to avoid the economic uncertainty that can come with sharp currency movements.

So, while the era of a global fixed system like Bretton Woods is over, the principles of fixing and pegging remain widespread, particularly among smaller and emerging-market economies. The U.S. dollar, though no longer pegged to gold, also remains a dominant global anchor currency.

Conclusion: A Journey from Rigidity to a Mixed System

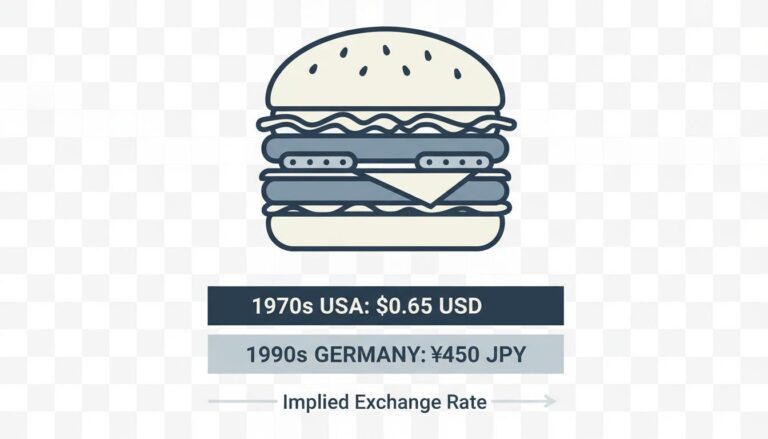

The fixed vs floating exchange rates history shows a clear evolution from the rigid, gold-anchored Bretton Woods system to a more complex, multipolar landscape. The collapse of the old order gave way to an era dominated by floating major currencies, granting nations newfound policy independence but also introducing greater volatility.

Yet, the debate is far from settled. Pockets of strict pegs persist, and the widespread practice of managed floating shows that many governments are still unwilling to leave their currency’s fate entirely to the market. This ongoing balancing act between stability and flexibility continues to shape global economics and the way we track historical exchange rates and their values over time.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system?

The Bretton Woods system, adopted after World War II, established fixed exchange rates by pegging major currencies to the US dollar—which was itself convertible into gold—providing decades of monetary stability until its collapse in 1971.

What is the main difference between fixed and floating exchange rates?

Fixed exchange rates are set by government or central bank intervention, pegging a currency to another asset, while floating exchange rates are determined by market forces such as supply and demand.

Why did countries move away from fixed exchange rate systems?

Countries shifted towards floating rates to gain monetary policy independence, respond to global capital flows and inflation, and reduce the vulnerability to speculative attacks when fixed pegs became unsustainable.

What is a managed float or dirty float exchange rate system?

A managed float (dirty float) is a system where the exchange rate is mostly determined by market forces, but the central bank occasionally intervenes to prevent excessive fluctuations or achieve policy goals.

Are there still countries using fixed exchange rates today?

Yes, some countries, especially small or trade-dependent economies such as members of the CFA franc zone and Hong Kong SAR, maintain currency pegs or fixed exchange rate arrangements.