The Role of Capital Controls in the Bretton Woods Era

After the economic chaos of the Great Depression and World War II, global leaders sought a new international financial system built on stability, not speculation. The framework they created, known as the Bretton Woods system, aimed to foster global trade while giving nations the power to protect their domestic economies from volatile financial flows.

The secret to this delicate balance was a foundational, yet often overlooked, element: the widespread use of capital controls under Bretton Woods. These regulations were not a flaw in the system but a core feature, deliberately designed to subordinate international finance to national economic goals like full employment and stable growth.

What Were Capital Controls and Why Were They Essential?

Capital controls are simply laws or regulations that restrict the cross-border movement of money for investment, borrowing, or other financial purposes. During the Bretton Woods era (1944–1971), these measures were institutionalized as a key pillar of the international economic order.

The architects of the system, most notably John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White, had witnessed the destructive capital flight and currency speculation of the interwar years. They believed that for a new system to succeed, it needed to differentiate between two types of international transactions:

- Current Account: The flow of money for trade in goods and services, which was to be encouraged and kept free.

- Capital Account: The flow of money for investments and financial speculation, which was to be managed and restricted.

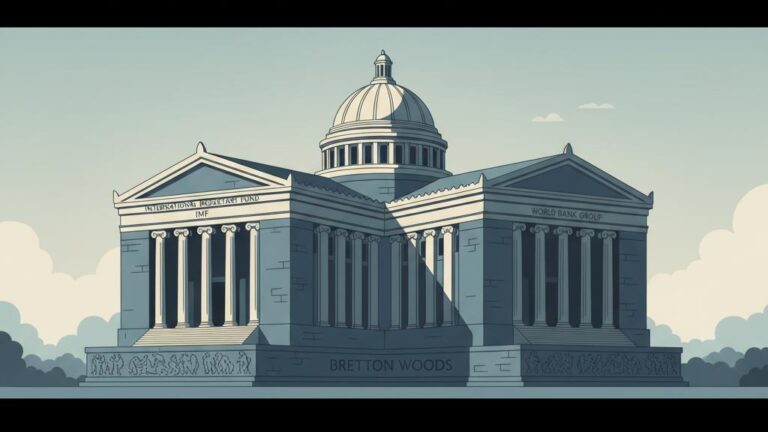

This separation was a radical departure from the pre-war gold standard. Under the Bretton Woods Agreements, member countries were explicitly granted the right to control capital movements, a right institutionalized and overseen by the newly formed International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The Purpose of Capital Controls in the Bretton Woods System

The primary goal was to create a stable environment where governments could pursue domestic policy objectives without fear of external disruption. By limiting the sudden inflow or outflow of capital, these controls served several critical functions:

- Preventing Destabilizing Speculation: Controls made it difficult for speculators to bet against a currency, preventing the kind of currency crises that had plagued the 1920s and 1930s.

- Protecting National Policy Autonomy: Governments could focus on achieving full employment and funding social welfare programs without having to raise interest rates to prevent capital from fleeing abroad.

- Supporting Fixed Exchange Rates: The system’s stability depended on member countries pegging their currencies to the U.S. dollar. Capital controls were the essential buffer that made these fixed but adjustable exchange rates viable.

Without these restrictions, speculative attacks could have quickly depleted a nation’s foreign reserves, forcing unwanted currency devaluations and undermining the entire system.

How Capital Controls Under Bretton Woods Were Implemented

Governments used a variety of tools to manage cross-border financial flows. These weren’t a single, uniform policy but a toolkit that countries could adapt to their specific needs. The history of financial regulation during this period shows a range of common methods.

Some of the most frequently used forms of capital controls included:

- Restrictions on Purchasing Foreign Assets: Limiting the ability of citizens and corporations to buy stocks, bonds, or real estate abroad.

- Taxes on Cross-Border Transactions: Imposing a tax on financial transactions that moved money out of the country, making it less profitable.

- Quantitative Limits: Setting explicit caps on the amount of money that could be moved across borders for investment purposes.

- Administrative Barriers: Requiring government approval for moving funds abroad, creating a bureaucratic process that could slow or stop large transfers.

These measures effectively insulated domestic economies, allowing them to maintain the stability required by the Bretton Woods framework.

The Economic Impact: Stability at a Cost

The effectiveness of capital controls during the Bretton Woods era is widely acknowledged in economic history. They were a key factor in the post-war economic boom, contributing to decades of growth and stability by insulating economies from international financial shocks.

This stability allowed governments to prioritize full employment and build robust social welfare states. However, this regulated system was not without its costs and trade-offs.

Benefits and Drawbacks

Quantitative research has shown that while these controls provided stability, they also came at a price. According to a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), global output might have been about 0.5% higher with fully open capital markets.

The most significant costs were borne by the United States. To support the system and the economic recovery of its Cold War allies, the U.S. accepted widespread capital controls abroad that hindered its own investment opportunities. This geopolitical priority led to a reduction in U.S. relative consumption growth compared to the rest of the world during this period.

The Erosion and Collapse of Capital Controls

By the late 1960s, the financial world had begun to change. The very success of the Bretton Woods system had led to greater global economic integration, which started to undermine the effectiveness of capital controls.

Several key factors contributed to their decline:

- Growing Private Capital Markets: The emergence of offshore markets, notably the Eurodollar market, created venues for U.S. dollars to be traded outside the reach of American regulators.

- Persistent Imbalances: The United States ran persistent balance of payments deficits, flooding the world with dollars and putting immense pressure on the system’s fixed exchange rates.

- Increased Speculative Pressure: As financial markets grew more sophisticated, investors found ways to circumvent controls and place massive bets against currencies they believed were overvalued.

These mounting pressures made the system of fixed rates and strong capital controls increasingly untenable. In 1971, the Nixon administration suspended the U.S. dollar’s convertibility into gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system. This act ushered in the modern era of financial liberalization, deregulation, and floating exchange rates.

Conclusion: The Legacy of a Regulated Era

The role of capital controls under Bretton Woods was to stabilize national economies, empower domestic policymaking, and maintain a predictable system of fixed exchange rates. For over two decades, they successfully shielded countries from the volatility of international finance, allowing for an unprecedented period of shared prosperity and growth.

Their eventual collapse marked a pivotal shift in the history of financial regulation, leading to the highly globalized and interconnected financial world we know today. Understanding this chapter is essential for grasping the full story of the history and demise of the Bretton Woods system and the ongoing debate between financial regulation and liberalization.

Frequently Asked Questions

What were capital controls, and why were they implemented under the Bretton Woods system?

Capital controls were regulations restricting international financial flows to protect domestic economies from volatile markets and speculative attacks. Under Bretton Woods, they enabled nations to pursue economic stability, full employment, and fixed exchange rates without risking sudden capital flight or destabilizing speculation.

How did the Bretton Woods system use capital controls differently from the gold standard?

Unlike the gold standard, which required both current and capital account convertibility, Bretton Woods allowed nations to restrict capital movements. This supported stability and policy autonomy while promoting trade and a more flexible international monetary system.

What were the effects of capital controls on the global economy during Bretton Woods?

Capital controls improved global economic stability, enabled governments to manage postwar recovery, and supported domestic growth policies. However, they also imposed costs such as reduced optimal resource allocation and, in the U.S. case, lower relative consumption growth.

Why did capital controls and the Bretton Woods system ultimately collapse?

By the late 1960s, pressures from greater global capital mobility, persistent imbalances, and the growth of private financial markets eroded the effectiveness of controls. This led to repeated currency crises and, eventually, the abandonment of fixed exchange rates in the early 1970s.