The Impact of WWI on Global Exchange Rates and Currency Markets

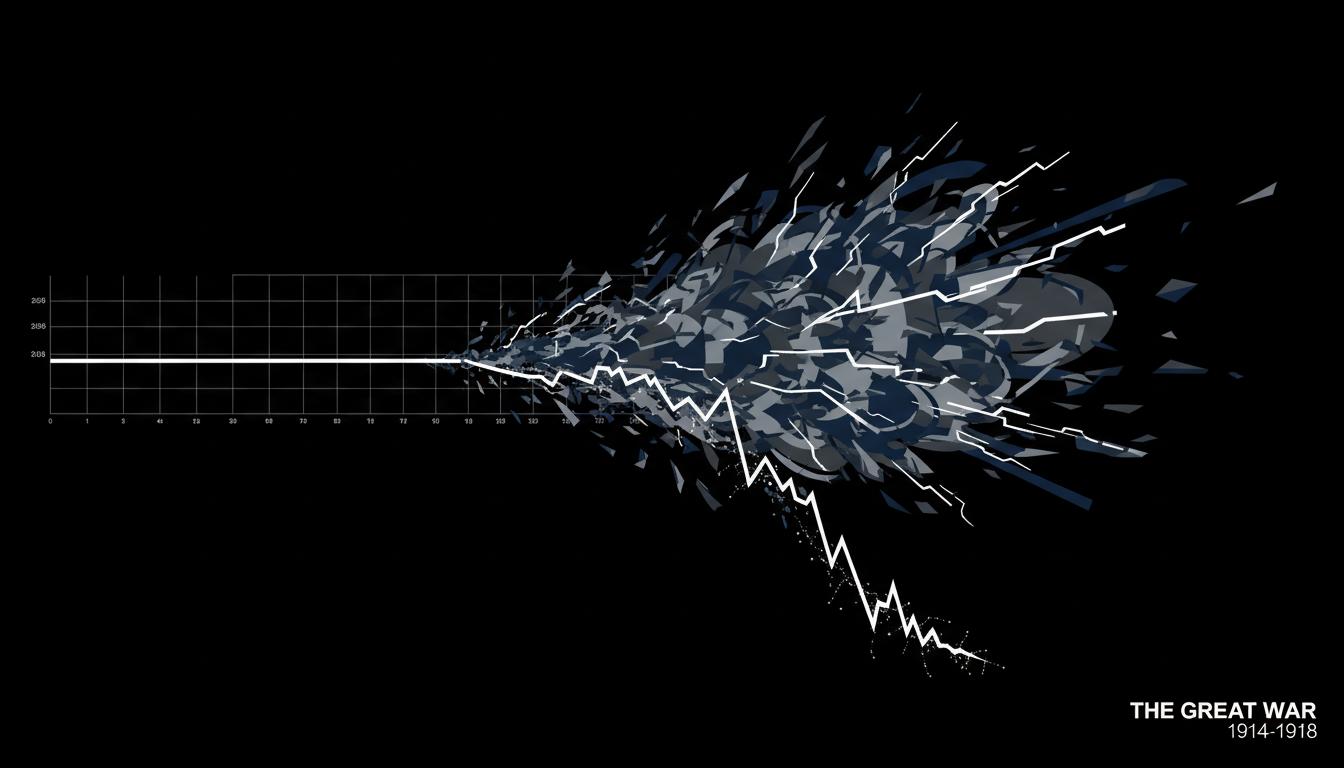

Before 1914, the world of international finance operated with a remarkable degree of stability. Major economies adhered to the gold standard, a system that pegged currency values directly to gold, creating predictable and reliable exchange rates. This era of calm was shattered by the outbreak of World War I, a conflict that fundamentally reshaped global monetary policy and demonstrated the profound ww1 impact on exchange rates for decades to come.

The war forced belligerent nations to abandon the gold standard, unleashing unprecedented currency volatility and devaluation. To finance the immense costs of the conflict, governments resorted to massive debt and money printing, measures that severed the link between currency and tangible assets. This shift marked the beginning of the end for the classical gold standard and ushered in a new, more chaotic era of international finance.

The Great Unraveling: Abandonment of the Gold Standard in WWI

The classical gold standard was the bedrock of pre-war international finance. It ensured that currencies were convertible into a fixed amount of gold, which in turn created a system of fixed exchange rates between participating countries. This stability facilitated international trade and investment, creating a predictable economic environment.

With the start of the war, this system became unsustainable. The primary reason for the abandonment of the gold standard in ww1 was the astronomical cost of the conflict.

- Unprecedented Military Spending: Governments needed to fund armaments, troop mobilization, and economic support for allies on a scale never seen before. Tax revenues alone were woefully insufficient.

- Need for Financial Flexibility: Sticking to the gold standard would have severely restricted a nation’s ability to finance its war effort. Gold reserves were limited, but the need for spending was not.

- Suspension of Convertibility: Nations like Great Britain, France, and Germany quickly suspended the convertibility of their currencies into gold. While they pledged to restore the pre-war system after the conflict, this promise would prove impossible for most to keep.

This suspension effectively turned these currencies into fiat money—backed only by the government’s decree rather than a physical commodity. This decision was a critical first step toward the currency chaos that would define the war and its aftermath.

War Finance and Currency: Fueling the Conflict, Debasing the Money

Once freed from the constraints of gold, governments employed aggressive strategies of war finance and currency manipulation to fund their military campaigns. This primarily involved two interconnected actions: massive debt issuance and reliance on central banks.

Governments dramatically expanded their national debt by issuing vast quantities of war bonds to the public and financial institutions. When that wasn’t enough, they turned to their central banks. In the United States, the newly formed Federal Reserve played a crucial role by maintaining low interest rates and easing credit to help the Treasury sell its war bonds.

This process led to a huge expansion of the money supply, which inevitably triggered significant inflation. As more money chased a limited supply of goods, prices rose, and the purchasing power of each unit of currency declined.

The Rise of the U.S. Dollar

While European currencies were severed from gold, the U.S. dollar remained linked to the precious metal. This unique position, combined with America’s robust economic performance as a supplier to the Allies, dramatically elevated the dollar’s international standing. It became a preferred medium of exchange and a safe-haven currency, setting the stage for its eventual dominance in the global financial system.

How the WW1 Impact on Exchange Rates Mirrored the Battlefield

During the war, currency markets became intensely sensitive to military developments. The uncertainty of the conflict led to frequent and dramatic fluctuations in exchange rates, as traders and investors desperately sought information to predict the war’s outcome. The value of a nation’s currency became a direct reflection of its perceived military strength.

Foreign exchange traders closely monitored news from the front lines. Key metrics included:

- Battle Outcomes: A significant victory could cause a nation’s currency to strengthen, while a major defeat would send it tumbling.

- Military Casualties: Traders on both the Western and Eastern fronts tracked casualty figures as a grim indicator of a country’s long-term ability to sustain its war effort.

A nation suffering heavy losses or battlefield setbacks would see its currency depreciate as market confidence waned. Even neutral countries like Switzerland, which traded with both sides, saw their exchange rates react to the shifting tides of the war. This period provides a stark example of how geopolitical events have long been central to tracking historical exchange rates.

Currency Devaluation in WWI: The German Mark’s Collapse

While most belligerent nations experienced inflation and currency weakness, Germany’s situation was particularly severe, culminating in one of history’s most infamous hyperinflationary episodes. The process of currency devaluation in ww1 began during the conflict and accelerated dramatically in its aftermath.

In 1914, the German Reichsmark ceased to be freely exchangeable for gold, and over the course of the war, “Papiermark” (paper mark) supplanted gold-backed currency. The combination of immense war debt, crippling reparation payments imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, and continued reliance on the printing press destroyed its value. By the early 1920s, the Papiermark was in freefall, leading to hyperinflation that rendered official exchange rates meaningless and wiped out the savings of the German middle class. This crisis necessitated multiple currency reforms, eventually leading to the introduction of the Rentenmark in 1923 and the Reichsmark in 1924.

Necessity Money and Eroding Trust

The instability wasn’t limited to national currencies. In many occupied territories and localities, shortages of official coins and banknotes led authorities and even private businesses to issue their own “necessity money” (Notgeld in German). While intended to facilitate local commerce, these emergency currencies further undermined faith in the central government’s money, contributing to the broader financial chaos and paving the way for future historical currency crises.

The Post-War Legacy: Interwar Exchange Rate Volatility

After the armistice, the promise to return to the pre-war gold standard proved largely illusory. The economic landscape had been fundamentally altered. Nations were burdened with massive debts, their money supplies had ballooned, and their industrial capacity was damaged.

Attempts to restore pre-war parities were mostly disastrous. For instance, the French franc was significantly devalued after the war, causing huge losses for foreign investors, including British citizens who had purchased French war bonds. The period was characterized by persistent interwar exchange rate volatility, as countries struggled to find stability.

The interwar years saw:

- Competitive Devaluations: Countries deliberately devalued their currencies to make their exports cheaper and gain a trade advantage.

- Failed Cooperation: Attempts at international monetary cooperation were often short-lived and ineffective.

- Final Abandonment: The Great Depression of the 1930s was the final nail in the coffin for the restored gold standard, as countries abandoned it one by one to pursue independent monetary policies.

World War I did not just interrupt the gold standard; it exposed its fragility in a world of total war and set in motion its eventual demise.

Conclusion

The impact of World War I on global exchange rates and currency markets cannot be overstated. The conflict shattered the century-old stability of the gold standard, replacing it with an era of fiat currencies, rampant inflation, and unprecedented volatility. It demonstrated how massive government spending financed by debt and money creation could debase a currency and how closely exchange rates could be tied to geopolitical conflict.

The war fundamentally reshaped the international financial order, weakening European currencies while elevating the U.S. dollar to a position of global prominence. The lessons learned from the financial chaos of WWI and the subsequent interwar period continue to influence modern monetary policy and our understanding of international economics today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did countries abandon the gold standard during World War I?

Belligerent nations suspended the gold standard primarily to finance the immense costs of the war. Maintaining gold convertibility would have restricted their ability to print money and issue debt, which was essential for funding military expenditures. The extreme fiscal pressure made adherence to the gold standard impossible.

How did World War I cause currency devaluation?

WWI caused currency devaluation through several mechanisms. Governments took on massive wartime debts and printed money to pay for them, leading to inflation. This expansion of the money supply, combined with a loss of public faith in unbacked currencies, caused their value to plummet, most notably in Germany and other Continental European countries after the war.

What was the impact of World War I on the U.S. dollar?

While European currencies became unbacked fiat money, the U.S. dollar remained convertible to gold throughout the war. This stability, coupled with America’s strong economic position, increased the dollar’s global stature and helped establish it as a leading international reserve currency.

How did military events affect exchange rates during WWI?

Foreign exchange traders treated battlefield outcomes as direct indicators of a nation’s economic future. Reports of military victories, defeats, and even casualty numbers on the Western and Eastern fronts caused immediate fluctuations in currency values, with nations performing poorly in the war seeing their currencies depreciate.