Tracking Ancient Currency Exchange: Roman Denarius to Byzantine Solidus

Imagine a Roman merchant in the bustling port of Antioch, trying to trade a shipment of olive oil for Parthian silk. His purse is filled with silver denarii, but the silk trader from the East deals in his own empire’s currency. How do they agree on a fair price without a digital screen flashing live market data? This scenario highlights the core challenge of ancient international trade, a puzzle solved not by complex algorithms but by simple, tangible value.

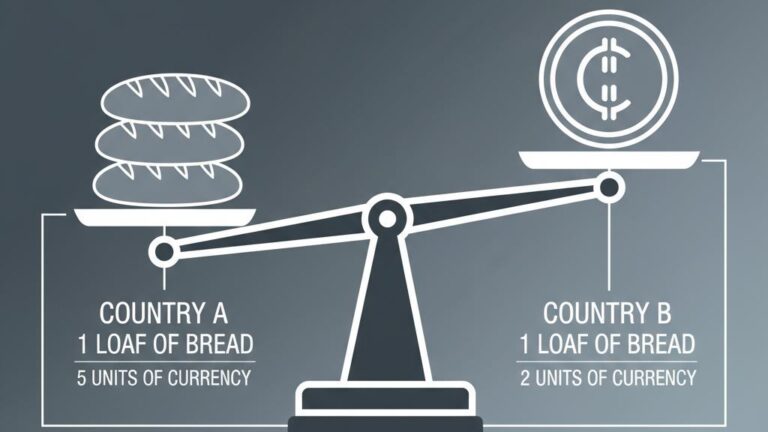

The solution was rooted in the precious metal content of the coins themselves. Unlike today’s fiat currencies, ancient currency exchange rates were fundamentally determined by the weight and purity of the gold or silver in a coin. This system, from the Roman Denarius to the later Byzantine Solidus, created a relatively stable and predictable foundation for commerce across empires, even as it faced its own unique set of challenges.

The Metal Standard: How Intrinsic Value Governed Ancient Economies

Before the advent of standardized coins, trade relied on barter or commodity-based systems. Civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and India used goods like barley and other grains as units of account to measure labor and value. While effective for local economies, these systems were cumbersome for long-distance trade.

Silver and gold emerged as the preferred commodities for international commerce due to their portability, divisibility, and universal appeal. In ancient Babylon, a sophisticated system of exchange based on silver functioned as an early form of currency. Temples played a crucial role, often fixing the exchange rates between key commodities like barley and silver, which helped organize and finance foreign trade.

The true revolution in commerce began around 600 BC in Lydia (modern-day Turkey), where the first coins were minted. This innovation marked a critical step in standardizing transactions and simplifying the calculation of historical exchange rates.

The Roman Denarius as an International Benchmark

The Roman Empire was instrumental in standardizing this metal-based system across a vast territory. The Roman silver denarius became a cornerstone of international trade. Its value was trusted because it had a relatively consistent weight and purity for long periods.

- Standard Weight: A Roman denarius weighed approximately 3.9 grams of silver.

- Basis for Exchange: This known weight and purity served as a reliable basis for calculating exchange rates with the currencies of other empires, such as the Parthian Empire.

- Long-Term Dominance: The stability of Roman coinage helped facilitate trade along vast networks, connecting diverse economies.

This reliance on intrinsic value meant that for many centuries, from Roman times through the Middle Ages, most of Europe operated under a silver standard. Silver was the primary metal for taxation and long-distance trade, creating a long era of relative monetary stability compared to modern systems.

Calculating Ancient Currency Exchange Rates: A Practical Example

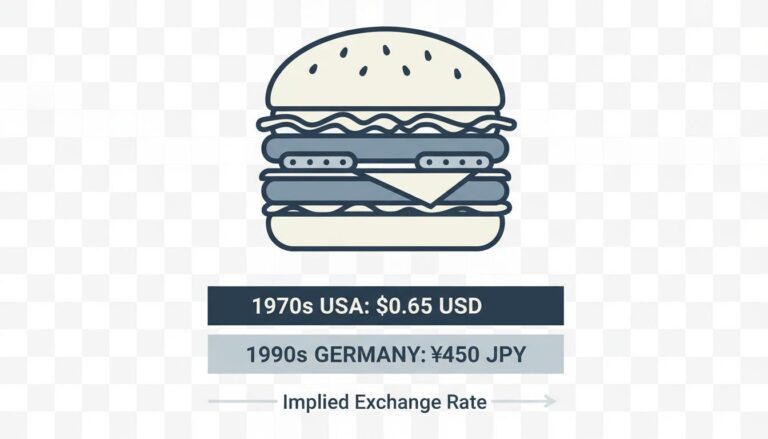

Calculating an exchange rate in the ancient world was a matter of metallurgy and mathematics, not market sentiment. A merchant didn’t need to watch for fluctuations in supply and demand; they needed to know the metal content of the coins being traded. The exchange rate between different currencies was simply a ratio of their precious metal weights, assuming equal purity.

Let’s return to our Roman merchant trading with a Parthian. The process would look something like this:

- Assess the Roman Coin: The merchant has a Roman denarius, known to contain a specific amount of silver.

- Assess the Parthian Coin: The Parthian silver coins were generally heavier, weighing approximately 4.2 grams.

- Calculate the Ratio: By comparing the metal content, the merchants could determine a fair exchange. One Roman coin would be worth slightly less than a Parthian coin, depending on purity.

Historical calculations show that one Roman coin could be exchanged for slightly less than one Parthian coin, based purely on their respective metal compositions. This straightforward, asset-backed system provided a level of predictability that was essential for the growth of trade routes and currency networks across continents.

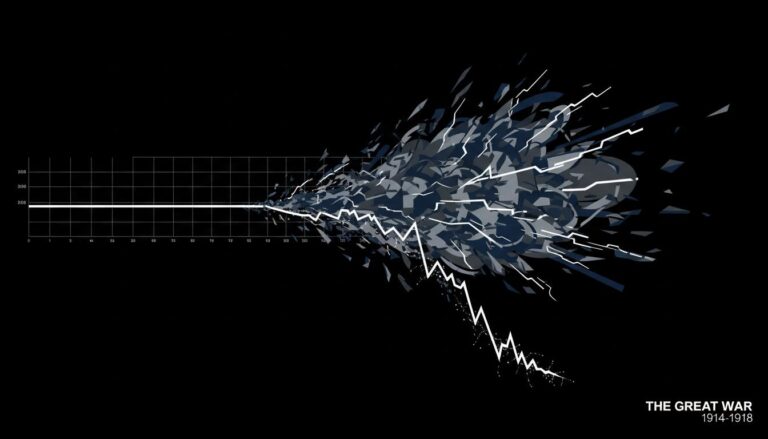

Forces of Fluctuation: Debasement and the Decline of Currency Value

While the metal standard provided stability, ancient exchange rates were not completely static. The value of coinage could and did change, primarily due to currency depreciation. This wasn’t caused by market forces but by the physical degradation and debasement of the coins themselves.

Several factors contributed to this decline in value, a key concern regarding currency value in the Middle Ages and antiquity:

- Wear and Tear: Over centuries of circulation, coins would naturally lose small amounts of metal, reducing their weight.

- Trimming and Sweating: Dishonest individuals would shave off small bits of metal from the edges of coins (trimming) or shake them in a bag to collect the resulting metal dust (sweating).

- Counterfeiting: Fake coins made from base metals with a thin silver or gold coating could infiltrate the money supply.

- Debasement: Rulers and governments would intentionally reduce the precious metal content of new coins, mixing in cheaper metals like copper. This allowed them to mint more coins from the same amount of silver or gold to fund wars or lavish projects.

This process is explained by Gresham’s Law, often summarized as “bad money drives out good.” When debased coins with less metal circulated alongside older, purer coins, people would hoard the more valuable “good” currency and spend the “bad,” causing the overall quality of currency in circulation to decline over time. This gradual debasement was a major factor in the later economic struggles of the Roman Empire and necessitated currency reforms, like the introduction of the more stable Byzantine solidus, a gold coin that held its value for centuries.

Managing a World of Currencies: From Reference Books to Early Banks

As trade expanded through the medieval period, the number of different currencies exploded. Every kingdom, duchy, and major city could mint its own coins, creating a bewildering landscape for merchants. The complexity became so great that specialized knowledge was required to conduct international business.

In 1633, a comprehensive currency guide was published in Antwerp listing over 1,400 different currencies with details on their weights, values, and designs. This reference book was an essential tool for any merchant, money changer, or banker. The sheer complexity of managing these diverse monetary systems was a key driver behind the creation of early financial institutions.

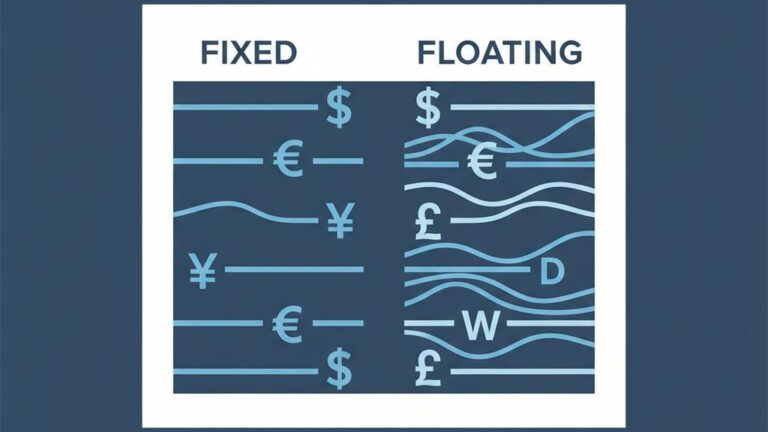

The establishment of the Amsterdam Bank in the 17th century was partly a response to this chaos. It became one of the first central banks, providing a reliable institution to settle international accounts. This marked a significant step away from simple metal-for-metal exchange and towards a more organized financial system, a precursor to the fixed vs. floating exchange rate systems of later centuries.

Even within the metal-based system, a clever mechanism called free coinage helped maintain stability. If a local exchange rate became unfavorable, a merchant could physically ship precious metal bullion abroad, have it minted into the local currency, and profit from the difference. As detailed by institutions like Sweden’s Riksbank, this arbitrage, though costly and time-consuming, limited how far exchange rates could deviate from their intrinsic metal values.

Frequently Asked Questions

How were exchange rates calculated in ancient Rome?

Ancient Roman exchange rates were calculated based on the intrinsic metal value and weight of coins. For example, Roman silver denarii (weighing 3.9 grams) were exchanged against other empires’ coins by comparing their metal purity and weight. If two coins had equal purity, the exchange rate could be determined by a simple ratio of their weights.

What caused exchange rates to change in ancient and medieval times?

Although ancient exchange rates were relatively stable, they changed due to currency depreciation. This resulted from physical wear, intentional trimming of metal from coins, counterfeiting, and deliberate debasement by rulers who minted coins with lower metal content. This phenomenon, known as ‘bad money drives out good money,’ caused gradual decreases in the value of circulating money.

What monetary system did medieval Europe use?

Medieval Europe operated primarily under a silver standard for many centuries, from ancient Roman times through the Middle Ages. Silver was the main medium for long-distance trade and taxation. The silver standard provided relative stability because the intrinsic metal value of currency was the primary determinant of exchange rates, a history tracked by organizations like the U.K. National Archives.

When did the first coins appear, and how did they affect exchange rates?

The first coins were minted in Lydia (modern-day Turkey) around 600 BC. These standardized coins became a more convenient means of exchange than barter or unmeasured metal, making it much easier to calculate and determine exchange rates between different regions. Gold and silver became especially important in international trade following the introduction of coinage.

Conclusion

From the silver denarius of Rome to the thousands of coins circulating in the Middle Ages, the system of ancient currency exchange rates was built on a simple premise: a coin was worth the metal it contained. This intrinsic value created a foundation of trust that allowed for predictable and stable international trade across vast empires and diverse cultures. While forces like debasement and depreciation introduced fluctuations, the metal standard provided a remarkably resilient framework for commerce for over a millennium.

Understanding this history reveals how fundamental principles of value have guided economies long before modern financial systems came into being. It provides essential context for appreciating the evolution of money and the complex world of historical purchasing power that shapes our global economy today.