Fiat Currency History: From Ancient IOUs to Modern Digital Dollars

The dollar bill in your wallet feels substantial, but at its core, it’s just a piece of paper and ink. Unlike coins of old, you can’t melt it down for its intrinsic value in gold or silver. So, what gives it the power to buy groceries, pay rent, and fuel the global economy? The answer lies in one of the most significant financial innovations in human history: fiat currency.

This system, where money is valuable simply because a government declares it to be, is the bedrock of modern finance. Understanding the fascinating fiat currency history reveals a long and often turbulent journey from tangible commodities to abstract trust. This guide explores that evolution, from the earliest paper notes in Imperial China to the complex digital dollars that move around the world today.

What Is Fiat Currency? A Foundation Built on Trust

At its simplest, what is a fiat currency is government-issued money that is not backed by a physical commodity like gold or silver. The word “fiat” comes from the Latin for “let it be done,” reflecting its value by government decree. Instead of being redeemable for a precious metal, its worth is derived from the collective trust and confidence the public has in the issuing government.

When a government declares a currency as “legal tender,” it legally obligates all parties within its borders to accept it as payment for debts, taxes, and goods. This legal backing, combined with effective management by a central bank, creates the foundation for its value.

Key characteristics of a fiat currency system include:

- No Commodity Backing: It has no intrinsic value; it cannot be exchanged for a set amount of gold, silver, or another commodity.

- Government Decree: It is established as money by law, making it legal tender.

- Central Bank Regulation: Its supply and value are managed by a central monetary authority, like the U.S. Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank.

- Value Based on Trust and Stability: Its purchasing power depends on supply and demand, the stability of the issuing government, and public faith in its economic management.

Nearly all major world currencies today, including the U.S. Dollar, the Euro, and the Japanese Yen, are fiat currencies.

The Precursors to Fiat: From Barter to Commodity-Backed Money

To appreciate the revolutionary nature of fiat money, it’s essential to understand what came before it. Early human societies relied on barter, the direct exchange of goods and services. However, this system was incredibly inefficient, as it required a “coincidence of wants”—each party had to possess something the other desired at the exact same time.

To overcome this, societies developed commodity money, where certain goods with inherent value were used as a medium of exchange. Gold, silver, copper, salt, and even shells became early forms of money because they were durable, divisible, and widely accepted as having value.

These commodities served as stable stores of value and reliable units of account, paving the way for more complex economies. For centuries, the value of money was intrinsically tied to the tangible worth of the material it was made from.

The Dawn of Government-Issued Money: Uncovering Fiat Currency History

The transition from heavy coins to weightless paper was a gradual process marked by innovation, skepticism, and economic necessity. The true history of paper money and fiat systems began not in the West, but in medieval China.

The First Fiat Currency: A Chinese Innovation

The earliest known use of a true fiat currency dates back to 11th-century China during the Song dynasty. Initially, merchants began issuing paper notes as representative money—essentially IOUs that could be redeemed for the heavy coins they held in reserve. These notes were more convenient and safer to carry for large transactions.

Over time, the government took control of this system and began issuing its own paper money. Crucially, these government notes gradually lost their direct link to commodity reserves, becoming the world’s first fiat currency. The Venetian explorer Marco Polo was astounded when he visited Yuan-dynasty China in the 13th century, describing in detail how the Emperor could create wealth from the bark of mulberry trees, a concept alien to Europeans at the time.

Early Experiments in the West

Europe’s journey toward fiat money was more fragmented. In the 17th century, Sweden began circulating government-issued notes, and early American colonies used “bills of credit” as a form of paper currency. However, these were often viewed with suspicion and were typically tied to promises of future payment in gold or silver.

These early experiments demonstrated the potential convenience of paper money but also highlighted the immense risk if the issuing authority’s credibility faltered.

The American Revolution’s Cautionary Tale: The Continental

One of the most infamous early examples of fiat money was the “Continental,” issued by the Continental Congress to finance the American Revolutionary War. With no power to tax and no gold reserves, Congress printed these bills en masse to pay soldiers and buy supplies.

However, without a strong central authority to back them, public confidence quickly evaporated. The currency suffered from massive inflation, and its value plummeted, giving rise to the enduring phrase “not worth a Continental.” This disastrous experience shaped the U.S. Constitution, which included strict controls on monetary policy and instilled a deep-seated distrust of unbacked paper money that would last for generations. The story of the Continental dollar remains a classic lesson in the importance of trust for a fiat currency.

The Global Shift: How the World Transitioned to Fiat Systems

Despite early failures, the practical needs of growing economies and the pressures of wartime financing continually pushed governments away from the rigid constraints of commodity-backed money. The government-issued money history of the 19th and 20th centuries is defined by this slow but inexorable shift.

Key U.S. Milestones on the Road to Fiat

The United States, scarred by the Continental, was cautious in its adoption of paper money. However, several key events forced its hand and paved the way for the modern fiat dollar.

- The Civil War and “Greenbacks”: To fund the immense costs of the Civil War, the U.S. government issued paper notes known as “Greenbacks.” These were not backed by gold and derived their value solely from government decree, making them one of America’s first widespread experiments with fiat currency.

- The Emergency Banking Act of 1933: During the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt took a major step in severing the link between the dollar and gold. The act ended the ability of U.S. citizens to exchange their dollars for gold, effectively making gold an asset for international settlement rather than a domestic currency backing.

- The 1971 “Nixon Shock”: The final break occurred on August 15, 1971. Facing economic pressures, President Richard Nixon officially announced that the U.S. would no longer redeem its dollars for gold held by foreign governments. This act, known as the Nixon Shock, unilaterally dismantled the Bretton Woods system and moved the entire global financial system onto a fiat standard.

This final move marked the definitive transition to fiat for the U.S. dollar and, by extension, for most of the world’s currencies that were pegged to it.

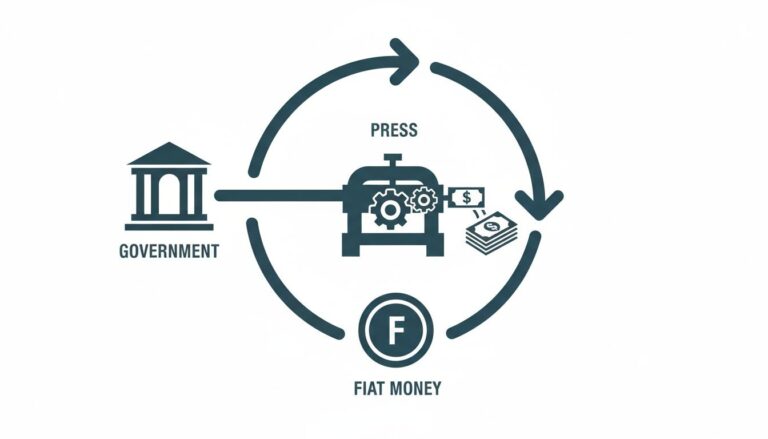

How Fiat Currency Works: The Modern Monetary Machine

Today’s fiat currency system is a complex engine managed by central banks to promote economic stability and growth. Its value is not left to chance but is actively influenced through sophisticated policy tools.

The Role of Central Banks

Central banks, such as the Federal Reserve, are the stewards of a nation’s fiat currency. Their primary mandate is typically to control inflation and maintain stable employment. They achieve this through monetary policy, which includes several key mechanisms:

- Open Market Operations: The buying and selling of government securities to increase or decrease the money supply in the banking system, which influences short-term interest rates.

- Reserve Requirements: Regulations that dictate the minimum amount of capital that commercial banks must hold in reserve rather than lend out.

- Interest Rate Management: Setting a target interest rate (like the Fed Funds Rate) to influence the cost of borrowing and lending throughout the economy.

The Pillars of Value: Why Is Money Fiat?

The fundamental reason why is money fiat today is flexibility. Unlike a gold standard, which limits a country’s money supply to its gold reserves, a fiat system allows a government to expand or contract the money supply to respond to economic needs. This agility is crucial for managing recessions, stimulating growth, and navigating financial crises.

The value of this money rests on three pillars:

- Legal Tender Laws: The government legally requires its acceptance for all debts, public and private, creating a constant demand for the currency.

- Collective Trust: Widespread public faith in the political and financial stability of the issuing authority ensures that people will continue to accept it in exchange for real goods and services.

- Central Bank Stewardship: The perception that the central bank is a competent and independent manager of the currency’s value is critical for maintaining long-term confidence.

The Double-Edged Sword: Advantages and Disadvantages of Fiat Currency

While fiat currency is now the global standard, it is a system with both powerful benefits and significant inherent risks. Its flexibility is its greatest strength and its most profound weakness.

The Benefits of a Flexible System

- Economic Crisis Management: Central banks can increase liquidity and lower interest rates to combat recessions, a flexibility not possible under a rigid gold standard.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Fiat money is far cheaper to produce than commodity money, which requires costly mining and storage of precious metals.

- Policy Management: It gives governments a powerful tool to influence credit, liquidity, and interest rates to pursue economic policy goals like stable prices and maximum employment.

The Inherent Risks and Dangers

- Inflation Risk: Since there is no theoretical limit to the amount of fiat money that can be printed, governments may be tempted to create too much, eroding its purchasing power through inflation. Over time, this can lead to a significant decline in the historical purchasing power of a currency.

- Dependence on Trust: A fiat currency’s value can collapse if the public loses faith in the government or central bank. Political instability, war, or gross economic mismanagement can trigger this loss of confidence.

- The Specter of Hyperinflation: In extreme cases, the rapid and uncontrolled printing of money can lead to hyperinflation, where a currency becomes virtually worthless overnight. History is filled with historical currency crises, from the Weimar Republic in the 1920s to modern hyperinflation examples like Zimbabwe, that serve as stark warnings of fiat mismanagement.

The Future of Money: Fiat in the Digital Age

The history of money is a story of continuous evolution, and the era of fiat is no different. As technology reshapes the financial landscape, government-issued money faces new challenges and opportunities.

The Current Status: Fiat’s Global Dominance

Today, fiat currency completely dominates global finance. Nearly every nation operates a fiat money system, and international trade is conducted almost exclusively using major fiat currencies like the U.S. dollar, which has remained the world’s primary reserve currency since the 20th century. This system has enabled unprecedented global economic integration and growth.

New Challengers: The Rise of Cryptocurrencies

The 21st century has introduced a radical new concept: decentralized digital currencies like Bitcoin. These cryptocurrencies present a fundamental challenge to the fiat model. Whereas fiat money has an unlimited supply controlled by a central authority, currencies like Bitcoin often have a fixed, finite supply governed by a decentralized computer network.

Economists and policymakers continue to debate whether cryptocurrencies are a viable alternative to fiat or simply a speculative asset class. Regardless, their existence has forced a global conversation about the nature of money and the role of governments in controlling it.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a fiat currency?

Fiat currency is government-issued money that is not backed by a physical commodity like gold or silver. Its value comes from legal tender laws and the public’s trust in the stability and credit of the issuing government.

When and where was the first fiat currency used?

The first true fiat currency appeared in 11th-century China during the Song dynasty. The government issued paper notes that were not directly redeemable for a fixed amount of a commodity, relying instead on its authority for their value.

Why do governments use fiat currency instead of gold-backed money?

Governments prefer fiat currency because it offers greater flexibility to manage the economy. It allows central banks to control the money supply, manage interest rates, and respond to financial crises like recessions in ways that are impossible under a rigid gold standard.

What risks are associated with fiat currency?

The primary risks are inflation and hyperinflation, which occur when a government creates too much money, eroding its purchasing power. Its value is also entirely dependent on public trust; if faith in the issuing government collapses, the currency can become worthless.

How did the US become a fiat currency nation?

The U.S. transitioned to a full fiat system in stages. Key steps included issuing “Greenbacks” during the Civil War, ending domestic gold redeemability in 1933, and officially severing the final link to the gold standard for international transactions in 1971 under President Nixon.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Fiat Currency

The history of fiat currency is a remarkable journey from the tangible value of precious metals to the abstract power of collective trust. This evolution was driven not by choice but by necessity, as growing economies and global crises demanded a more flexible and responsive form of money.

While fraught with risks like inflation and dependent on prudent stewardship, the fiat system has become the engine of modern global commerce. As we move further into a digital age, the principles of government backing and public confidence established over centuries will continue to shape the future of money, ensuring that this grand economic experiment continues to evolve.