The Origin of Paper Money: China’s Flying Money

Long before the invention of credit cards or digital transfers, merchants in Tang dynasty China faced a weighty problem: how to move vast sums of money across a sprawling empire. The only currency available was heavy copper coinage, making large transactions a logistical nightmare. This challenge sparked a revolutionary financial innovation, marking the beginning of China’s flying money history and paving the way for the world’s first paper currency.

This early form of paper note, known as feiqian or “flying money,” was not true currency but a negotiable instrument that allowed value to travel hundreds of miles with the speed of a messenger on horseback. This system solved a critical problem for a booming economy, laying the conceptual groundwork for the government-issued paper money that would transform global finance centuries later. The journey from these private certificates to state-backed bills is a pivotal chapter in the history of money.

The Emergence of ‘Flying Money’ (Feiqian) in the Tang Dynasty

Around 807 CE, the Tang dynasty’s economy was expanding rapidly, but its monetary system couldn’t keep up. Increased taxation and thriving internal trade created a severe shortage of copper coins, the primary medium of exchange. Transporting what little coinage was available was both dangerous and impractical for merchants conducting business across great distances.

In response to this commercial need, the concept of feiqian (飛錢) was born. This system was elegantly simple:

- A merchant would deposit his copper coins with a trusted agent—often a local government official or a powerful merchant family—in the capital city.

- In return, he received a written paper certificate or receipt detailing the amount deposited.

- The merchant could then travel to a regional outpost without carrying the heavy, cumbersome coins.

- Upon arrival, he would present the certificate to an associate of the agent and redeem it for the equivalent amount in local currency.

The term “flying money” perfectly captured its function. It allowed wealth to “fly” across the country, untethered from its physical metallic form. This innovation was a crucial lubricant for the Tang dynasty’s rapidly growing trade network.

From Private Tool to Government Oversight

Initially, feiqian was a private enterprise, and the Tang government viewed it with suspicion. Fearing a loss of control over the empire’s currency and financial system, officials first attempted to ban the practice. However, the economic necessity of these instruments was undeniable.

By 812 CE, the government reversed its stance and officially recognized flying money, bringing it under state regulation. Key government bodies, including the Ministry of Revenue and the Salt Monopoly Bureau, began supervising the issuance and verification of these certificates. While still not legal tender, feiqian became a state-sanctioned tool for remittance that remained in use until the subsequent Song dynasty.

A Monetary Leap: The Song Dynasty Paper Currency

While the Tang dynasty introduced the concept of paper remittance, it was the Song dynasty (960–1279) that took the revolutionary step of creating the world’s first true, government-issued paper currency. This marked a profound shift from a simple certificate of deposit to a widely accepted medium of exchange. The history of money in China shows a consistent pattern of innovation to solve the practical needs of a complex, commercialized society.

The transition began organically. In regions like Sichuan, a hub of commerce known for its iron coinage, private merchants started issuing their own paper notes, known as jiaozi. These notes were initially more convenient than carrying thousands of heavy iron coins for a single transaction. Recognizing the immense potential and the need for a more reliable system, the Song government stepped in.

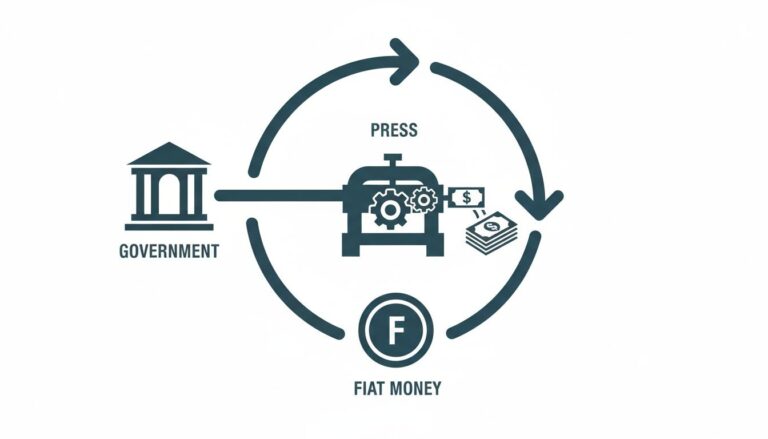

In 1024, the state nationalized the issuance of these notes, creating a standardized, government-backed paper currency. This was a pivotal moment not just for China, but for the world. For a deeper look at how governments adopt such systems, see our article on the transition to fiat money.

Key Features of Song Dynasty Paper Currency

The Song government implemented several sophisticated features to build public trust and ensure the functionality of its new paper money. These concepts laid the foundation for modern currency systems.

- State Backing: Unlike private notes, the government’s paper money was backed by reserves of metallic currency (primarily copper coins). Citizens could, in principle, exchange their paper notes for “hard” cash at designated government banks, which created essential public confidence.

- Intricate Designs for Security: To combat forgery, the bills were printed with complex designs featuring detailed images of houses, trees, and people. They were also stamped with multiple official seals, making them difficult to replicate with the technology of the time.

- Strict Regulation: The government controlled the currency’s circulation carefully. Early notes were often valid only within specific regions and for a limited term, typically three years, after which they had to be exchanged for new ones.

- Facilitating Commerce: The widespread adoption of paper money had a massive economic impact. It enabled large-scale transactions for everything from everyday goods to tax payments, fueling both internal trade and cross-border commerce along routes like the Silk Road. As one of the earliest forms of paper currency, its influence can be compared to the standardized coinage used in ancient currency exchange systems.

The Challenges of an Early Fiat System: Inflation and Forgery

Despite its brilliance, China’s early experiment with paper money was not without serious problems. The ability to create money by printing it, rather than mining it, introduced new and potent economic risks. Two major challenges emerged: inflation and counterfeiting.

As the Song government needed funds to finance military campaigns and other state expenditures, the temptation to print more money than its metallic reserves could support proved overwhelming. This overissuance led to devastating inflation. The most dramatic period occurred between the late 12th and early 13th centuries, when the supply of paper notes increased dramatically, causing prices to surge and eroding the value of the currency. This massive devaluation eroded public trust and destabilized the economy.

At the same time, counterfeiters were a persistent threat. Although the penalty for forgery was often death, the potential rewards were high enough to encourage criminals. The state constantly had to update note designs and recall old currency to stay ahead of counterfeit operations. This ongoing struggle highlights the inherent vulnerabilities of early paper money systems, a challenge that persists even in today’s modern fiat currency systems.

Later Developments and the Lasting Impact of China’s Flying Money History

The Mongol-led Yuan dynasty, which succeeded the Song, embraced and expanded the use of paper currency. The system so impressed the Venetian traveler Marco Polo that he described it with wonder in his writings, comparing the emperor’s ability to create money to the work of an alchemist turning paper into gold. However, the Yuan also fell prey to the allure of the printing press, issuing currency far beyond the economy’s capacity and triggering hyperinflation.

This long history of economic instability eventually led to a reversal. After repeated cycles of currency devaluation and mismanagement, the subsequent Ming dynasty largely abandoned paper money and returned to a more stable system based on metallic currency, primarily silver. It would be centuries before paper currency was successfully reintroduced in China.

Despite its eventual collapse, China’s invention of flying money and the world’s first true paper currency was a monumental achievement. The concepts pioneered during the Tang and Song dynasties—state backing, anti-forgery designs, controlled issuance, and redeemability—were centuries ahead of their time. They provided a blueprint that would eventually be adopted worldwide, forming the very foundation of modern monetary systems. As Columbia University’s Asia for Educators program notes, these developments were central to the Song’s commercial revolution. China’s early experience offered both a model for success and a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked currency creation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was ‘flying money’ (feiqian), and how did it work?

‘Flying money’ was a Tang dynasty negotiable instrument allowing merchants to deposit funds in one location and receive a certificate redeemable elsewhere, thus securely transferring large sums without moving physical coins.

How did Song dynasty paper currency differ from Tang dynasty flying money?

Song dynasty paper currency was government-issued, widely accepted as legal tender, and backed by state reserves, whereas Tang flying money was primarily a privately issued merchant remittance tool that lacked legal tender status.

Why did the use of paper money in China lead to inflation?

Successive governments printed excessive notes to finance spending, especially during wars, causing the currency’s supply to outpace its backing and triggering rapid price increases and a loss of public confidence in its value.

How did early Chinese paper money influence global monetary systems?

China’s systemic use of paper currency inspired similar approaches elsewhere and introduced concepts—such as government backing, standard designs, and note redemption—that are fundamental to today’s fiat currencies.

Why did China revert to metallic money after centuries of paper currency use?

Recurring hyperinflation, rampant counterfeiting, and mismanagement of paper money during the late Yuan and early Ming periods eroded confidence, prompting a return to coins, which were regarded as more stable and trustworthy.

Conclusion

The story of China’s flying money is more than a historical curiosity; it is the origin story of paper currency itself. Born from the practical needs of Tang dynasty merchants, feiqian evolved into the world’s first government-backed paper money under the Song dynasty, a financial tool that revolutionized commerce and governance. While this early experiment ultimately succumbed to the timeless economic pressures of inflation and mismanagement, its innovations were profound and enduring.

The principles developed over a thousand years ago in China—from certificates of deposit to state-guaranteed notes—created the conceptual framework upon which all modern paper and fiat currencies are built. Understanding this remarkable history provides essential context for appreciating the complexity and power of the financial systems we rely on today.