The SDR (Special Drawing Rights): Bretton Woods’ Monetary Instrument

In the complex world of international finance, few instruments are as unique or misunderstood as Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). Born from the pressures of a changing global economy, the special drawing rights history is deeply intertwined with the evolution of the post-war monetary system. They are not a currency you can hold in your hand, yet they play a critical role in stabilizing the world’s economies, especially during times of crisis.

At its core, the SDR is an international reserve asset created by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1969 to supplement the official reserves of its member countries. This article explores the origins, function, and modern relevance of the SDR, explaining how this unique monetary tool works and why it remains a key component of the global financial architecture.

The Origins and Special Drawing Rights History

The creation of the SDR was a direct response to the growing strains on the Bretton Woods system in the late 1960s. Under this system, the U.S. dollar was pegged to gold, and other currencies were pegged to the dollar. However, concerns grew about the world’s reliance on just two primary reserve assets: gold and the U.S. dollar.

A conservative U.S. monetary policy and the rigidities of the gold-dollar standard led to reserve shortages in many nations. The global community needed a new, neutral reserve asset to ensure there was enough liquidity to support expanding world trade and financial development. The SDR was designed to be that asset, redistributing liquidity globally and correcting the shortcomings of a system overly concentrated in gold and dollars.

From Gold Peg to Currency Basket

Initially, the SDR’s value was defined by a fixed weight in gold. One SDR was equivalent to 0.888671 grams of fine gold, which at the time was also the value of one U.S. dollar. This direct link to gold was short-lived.

After the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, the SDR’s valuation method had to change. It was redefined in terms of a basket of major international currencies, a system that continues today. This shift marked a significant evolution in its role, moving from a potential alternative to gold to a composite asset underpinning the IMF’s finances and serving as its official unit of account.

SDR IMF Explained: What Is It, Exactly?

It’s crucial to understand that an SDR is not a currency in the traditional sense. You cannot go to a bank and withdraw SDRs. Instead, it is a potential claim on the freely usable currencies of IMF member countries.

Think of it as a special kind of credit that central banks and governments can hold in their reserves. If a country faces a balance of payments crisis or needs to bolster its reserve position, it can exchange its SDRs with other member countries for hard currencies like the U.S. dollar or the Euro. This process is managed and facilitated by the International Monetary Fund, which acts as the intermediary.

Importantly, no private entities or individuals can hold or use SDRs. Their use is restricted to IMF members, the IMF itself, and a few specially designated international institutions.

SDR Currency Basket Components

The value of an SDR is determined daily based on a weighted average of a basket of five major currencies. The IMF reviews this basket every five years to ensure it reflects the relative importance of currencies in the world’s trading and financial systems. As of the most recent review, the basket comprises:

- U.S. Dollar (USD)

- Euro (EUR)

- Chinese Yuan (CNY)

- Japanese Yen (JPY)

- British Pound Sterling (GBP)

The inclusion of the Chinese Yuan in 2016 was a landmark decision, reflecting China’s growing prominence in the global economy. The weight of each currency in the basket is based on its share of international exports and its role as a widely used and traded currency.

Allocation and Use in Times of Crisis

The IMF allocates SDRs to its members in distinct tranches, typically during periods of global economic stress when additional liquidity is most needed. These allocations are distributed based on each country’s IMF quota, which is a measure of its relative size in the global economy. Major allocations throughout the special drawing rights history include:

- 1970–72: SDR 9.3 billion (Initial allocation)

- 1979–81: SDR 12.1 billion (Amid skepticism about the dollar)

- 2009: SDR 182.6 billion (In response to the global financial crisis)

- 2021: SDR 456.5 billion (The largest allocation ever, to combat the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic)

As of 2025, the total allocated SDRs stand at SDR 650.7 billion (approximately US$851.6 billion). The 2021 allocation was particularly impactful, providing much-needed, debt-free liquidity to developing and emerging economies. For some nations like Liberia and South Sudan, this allocation was equivalent to nearly 10% of their GDP.

Channeling SDRs for Development

In recent years, the IMF has developed mechanisms to channel SDRs from wealthier countries that may not need them to low-income nations that do. This is done through initiatives like the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) and the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST).

These trusts allow developing countries to access interest-free or low-interest loans to finance critical reforms and build resilience against economic shocks. According to the IMF, by September 2025, this channeling mechanism is projected to have facilitated approximately $39 billion in loans to 57 countries.

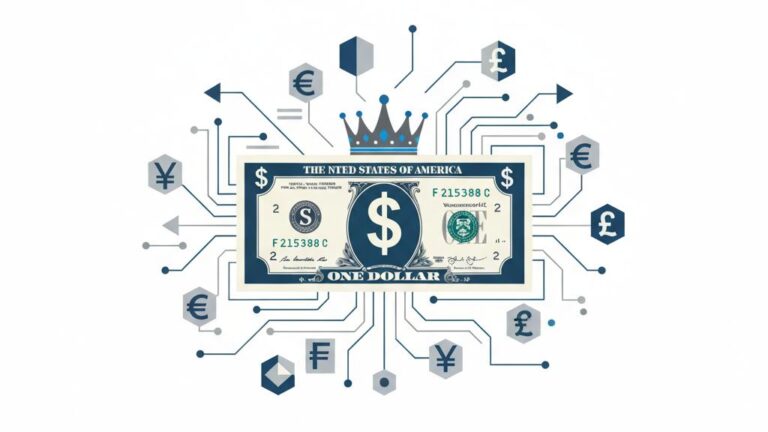

An Alternative to the World Reserve Currency?

For decades, economists have debated whether the SDR could serve as an alternative to the world reserve currency, a role long dominated by the U.S. dollar. Proponents argue that a system based on SDRs would offer greater stability through diversification and provide a source of liquidity not tied to the domestic policies of a single nation.

However, the SDR’s adoption as a global reserve standard has been limited for several key reasons:

- Limited Scope: SDRs can only be used in government-to-government transactions, lacking the infrastructure for private use in trade and finance.

- Allocation Method: Because allocations are based on IMF quotas, wealthier nations receive the largest share, though channeling mechanisms are starting to address this.

- Dominance of the Dollar: The U.S. dollar remains dominant in international markets, backed by the deep, liquid financial markets of the United States.

Despite these limitations, the unique characteristics of SDRs—being debt-free, unconditional, and not tied to strict loan conditions—make them an invaluable tool. As noted by experts at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), they represent an ongoing effort to enhance the elasticity of the international monetary system.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are Special Drawing Rights (SDRs)?

SDRs are international reserve assets created by the IMF in 1969 to supplement countries’ official reserves and support global liquidity. They are not a physical currency but represent a claim on a basket of five major currencies.

How is the value of the SDR determined?

The SDR’s value is based on a weighted average of a basket of five currencies: the U.S. dollar, Euro, Chinese Yuan, Japanese Yen, and British Pound. The IMF reviews the composition and weighting of this basket every five years.

How are SDRs allocated and who can use them?

The IMF allocates SDRs to member countries based on their economic size (IMF quotas). Only central banks, governments, and prescribed international institutions can hold and exchange them; they are not available to private individuals or companies.

Can SDRs replace the US dollar as the world reserve currency?

While SDRs have been discussed as an alternative, their limited adoption is due to several factors, including their restricted usage and the lack of infrastructure for private transactions. The U.S. dollar’s deep market liquidity and widespread use mean it remains the dominant global reserve currency.

How have SDRs been used in recent economic crises?

In 2021, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF made its largest-ever SDR allocation of about US$650 billion to boost global liquidity. This provided significant financial support, especially for developing and low-income countries, without adding to their debt burdens.

Conclusion

From its origins in the final years of the Bretton Woods system to its modern role in combating global financial crises, the Special Drawing Right has proven to be a resilient and adaptable monetary instrument. While not a “silver bullet” for all economic challenges, its ability to provide unconditional, debt-free liquidity makes it an indispensable tool for the International Monetary Fund and its member nations.

The history of the SDR is a testament to the ongoing effort to create a more stable and equitable international financial system. Understanding its function is key to appreciating the complex mechanisms that support the global economy, a story deeply rooted in the legacy of the Bretton Woods agreement.