The Great Depression and Deflation: How Prices Fell in the 1930s

The Great Depression is often remembered through stark images of stock market crashes and long unemployment lines. However, a less visible but equally destructive force was at play: a relentless, economy-crushing fall in prices. This phenomenon, known as the great depression deflation, created a devastating spiral where falling prices led to lower wages, higher debt burdens, and widespread financial ruin.

While cheaper goods might sound beneficial, the reality of the 1930s was far from it. As prices for everything from bread to cars collapsed, so did incomes, jobs, and the ability for people to pay their debts. This article explores the mechanisms of this deflationary crisis, its profound impact on everyday life, and the harsh lessons it taught the world about economic stability.

What is Deflation? A Primer

Deflation is the opposite of inflation. It is a persistent and broad decrease in the general price level of goods and services. When deflation occurs, the value of money increases, meaning each dollar can theoretically buy more than it could before.

However, this theoretical boost in purchasing power is often an illusion, as seen during the Great Depression. The era’s deflation was coupled with mass unemployment, severe wage cuts, and collapsing farm incomes. For the millions without a steady paycheck, the fact that goods were cheaper was irrelevant; they had no money to spend in the first place.

The Scale of Deflation During the Great Depression

The price collapse between 1929 and 1933 was staggering in its speed and scope. It represented the most severe deflationary period in modern American history, impacting every corner of the U.S. and global economy.

Plummeting Consumer and Wholesale Prices

The numbers illustrate a dramatic downturn. Key indicators of deflation include:

- Consumer Prices: The U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI), a measure of the average cost of a basket of consumer goods, fell by approximately 27% between 1929 and 1933. To understand how such figures are calculated, it’s helpful to see how economists are using CPI to adjust historical values.

- Wholesale Prices: The decline was even more severe for producers, with wholesale prices plummeting by around 32% during the same period.

- Annual Deflation Rate: In the single year of 1932, the deflation rate exceeded a catastrophic 10%.

A Collapse in Production and Trade

The falling prices were both a cause and a symptom of a broader economic shutdown. Industrial production in the United States nosedived by about 47% between 1929 and 1933.

Globally, the crisis was exacerbated by protectionist policies like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. These tariffs led to retaliatory measures from other nations, causing international trade to shrink by an astonishing over 60% from its 1929 peak.

The Human Cost: Unemployment and Lost Income

The economic devastation translated directly into human suffering. In the U.S., unemployment soared, peaking near 24.9% in 1933, meaning roughly one in every four workers was jobless. Some countries experienced even higher rates, reaching up to 33%.

For those who kept their jobs, wages were often slashed. As a result, personal incomes, corporate profits, and government tax revenues all declined steeply, starving the economy of necessary funds for spending and investment.

How Great Depression Deflation Created a Vicious Cycle

Deflation wasn’t just a symptom of the Depression; it was an active agent that made the crisis deeper and longer. Economists refer to this phenomenon as a “deflationary spiral”—a self-reinforcing cycle where falling prices lead to lower production, which leads to lower wages and demand, which leads to even lower prices.

The Crushing Burden of Debt

One of deflation’s most destructive effects was on debt. Loans are taken out in nominal dollar terms, and the payments remain fixed regardless of price changes. As prices and incomes fell, the real (inflation-adjusted) burden of debt skyrocketed.

A farmer who took out a mortgage in the booming 1920s suddenly had to repay it with dollars that were worth far more, while the price of his crops had collapsed. This dynamic led to mass defaults and bankruptcies among farmers and homeowners, fueling the crisis. The Federal Reserve has extensively documented how this debt-deflation cycle crippled the economy.

Business Failures and Wage Cuts

Businesses faced a similar trap. With falling prices and shrinking consumer demand, revenues plummeted. To survive, companies cut costs by slashing wages or laying off workers, which further reduced overall demand in the economy and put more downward pressure on prices.

Bank Failures and Credit Freezes

As individuals and businesses defaulted on their loans, banks suffered immense losses. This triggered bank runs, where fearful depositors rushed to withdraw their savings. Thousands of banks failed, erasing the life savings of millions and causing a severe contraction in the nation’s money supply, which only worsened the deflation.

History of Prices During the Great Depression: A Closer Look

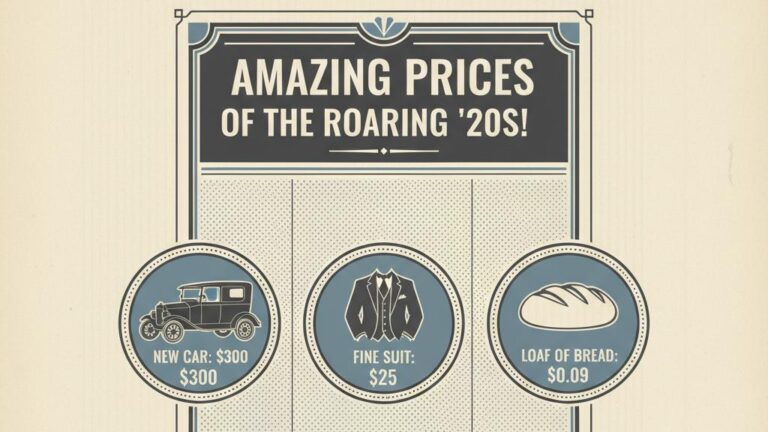

Examining the history of prices during the Great Depression reveals a painful paradox. While the cost of living dropped in nominal terms, the actual affordability of goods collapsed for a vast portion of the population. The era starkly contrasts with the rising cost of living in the 1920s pre-depression.

The Illusion of Affordability and Purchasing Power in the 1930s

The concept of purchasing power in the 1930s is complex. For someone on a fixed income, like a retiree with a pension, deflation did increase their purchasing power. Their income remained the same while goods became cheaper.

However, this was a tiny minority. For the millions of unemployed workers or farmers whose incomes had vanished, lower prices were meaningless. The real historical purchasing power of money depends on both prices and income, and with incomes in freefall, the ability to purchase goods declined sharply for most Americans.

What Was the Cost of a Loaf of Bread in the 1930s?

Everyday items provide a clear example of falling prices. The cost of a loaf of bread in the 1930s in the U.S. was a telling indicator:

- In the early 1930s, a loaf of bread typically cost around 7 to 9 cents.

- At the worst point of the Depression, the price dropped to as low as 6 cents.

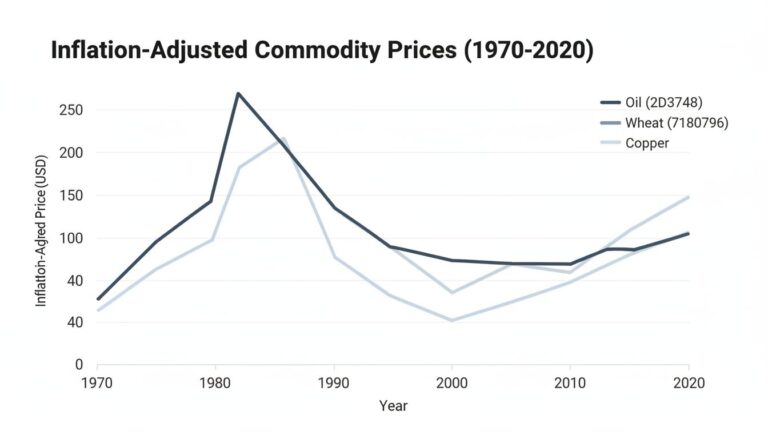

Similarly, prices for agricultural staples like milk, eggs, wheat, and cotton collapsed. This was disastrous for farmers, many of whom were driven off their land because they could no longer cover their costs or pay their debts.

Deflation vs. Inflation History: Lessons from the 1930s

The experience of the Great Depression fundamentally shifted economists’ views on the dangers of falling prices. In the great deflation vs. inflation history debate, the 1930s serve as the primary exhibit for why deflation is considered a more destructive economic force than moderate inflation.

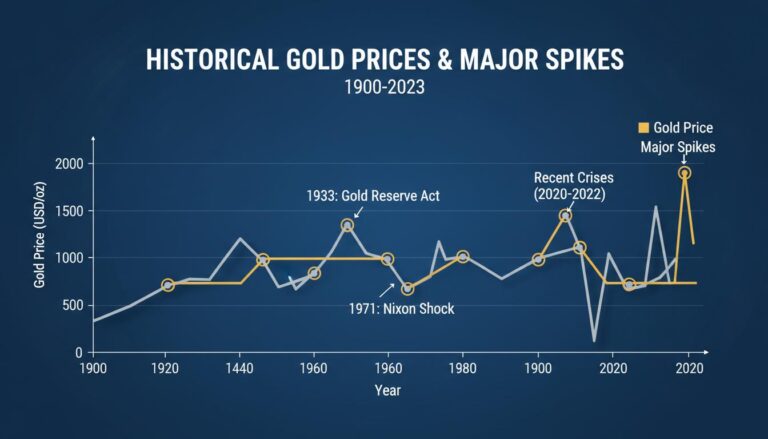

The Gold Standard’s Role

A key factor prolonging the crisis was the international gold standard, which pegged currencies to a fixed amount of gold. This system made it difficult for central banks to respond to the crisis. They could not easily expand the money supply to combat deflation without threatening their gold reserves.

As detailed by institutions like the St. Louis Federal Reserve, this monetary rigidity deepened the downturn. Countries that abandoned the gold standard earlier generally recovered faster.

Discouraging Spending and Investment

Deflation creates a powerful incentive to hoard cash and delay purchases. Why buy a car or invest in a new factory today if you expect prices to be 10% lower next year? This behavior causes consumer spending and business investment to grind to a halt, further depressing the economy.

The Road to Recovery: Escaping the Deflationary Trap

The recovery from the Great Depression’s deflation began only when governments took decisive action to break the spiral. In the United States, this recovery coincided with several key policies:

- Abandoning the Gold Standard: In 1933, the U.S. effectively abandoned the gold standard, allowing the currency to devalue and the money supply to expand.

- New Deal Programs: Government spending on relief and public works programs injected much-needed demand into the economy.

- Monetary Expansion: The Federal Reserve began to pursue policies aimed at increasing the money supply and ending deflation.

Ultimately, the massive government spending required for World War II conclusively ended the deflationary era and pulled the U.S. economy out of the depression.

Frequently Asked Questions

What caused deflation during the Great Depression?

Deflation was driven by a contraction in the money supply, widespread bank failures, collapsing demand, and adherence to the gold standard, which limited monetary policy responses.

How did deflation affect ordinary people in the 1930s?

While prices of goods like bread fell, mass unemployment and wage cuts meant most people’s purchasing power did not improve, and many faced financial ruin due to rising real debt burdens.

What was the cost of a loaf of bread during the Great Depression?

A loaf of bread cost around 7–9 cents in the early 1930s and dropped to 6 cents at the depression’s worst, although job loss often meant affordability was still out of reach for many.

How did countries recover from Great Depression deflation?

Countries that abandoned the gold standard, allowed their currencies to depreciate, and expanded monetary policy recovered faster from deflation and economic decline.

Why is deflation considered more damaging than inflation by economists?

Deflation discourages spending and investment, increases the real burden of debt, and can trigger widespread bankruptcies and economic stagnation, as seen during the Great Depression.

Conclusion

The great depression deflation stands as a stark reminder that falling prices are not always a sign of economic health. The 1930s demonstrated that a sustained deflationary spiral could be more damaging than inflation, trapping an economy in a cycle of declining incomes, rising debt, and mass unemployment.

By paralyzing spending, crushing debtors, and bankrupting businesses, deflation was a primary engine of the worst economic crisis in modern history. The lessons learned from this painful decade continue to shape economic policy and the global effort to maintain price stability today.