The Eurozone Debt Crisis: History and Economic Impact

Beginning in late 2009, a financial storm gathered over Europe, threatening to tear apart the very fabric of its single currency. This period of turmoil, known as the European sovereign debt crisis, exposed deep-seated vulnerabilities within the monetary union, pushing several nations to the brink of economic collapse. Understanding the eurozone debt crisis history is crucial to grasping the economic and political landscape of modern Europe.

The crisis was a complex web of rising government debt, investor panic, fragile banking systems, and prolonged economic stagnation. It highlighted structural flaws in the eurozone’s design and revealed years of fiscal mismanagement in several member states, leading to painful consequences that are still felt today.

The Deep Roots: Origins of the Eurozone Crisis

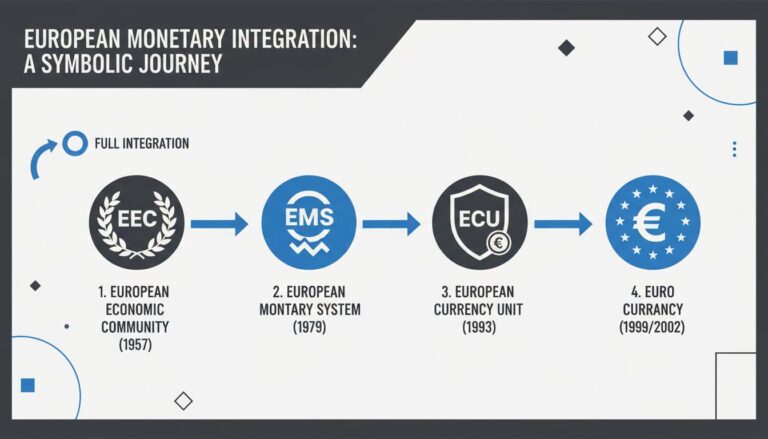

The seeds of the crisis were sown long before the panic of 2009. The framework of the euro itself, established by the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, contained vulnerabilities that would later be exposed.

Structural Flaws from the Start

The Maastricht Treaty set strict rules for countries wishing to join the euro: public debt could not exceed 60% of GDP, and annual budget deficits had to remain below 3% of GDP. However, many member states, including Greece, Italy, and Portugal, consistently failed to meet these targets, often without facing significant penalties.

A critical design flaw was the removal of currency devaluation as a policy tool. Before the euro, a country with a struggling economy could devalue its currency to make its exports cheaper and boost competitiveness. The creation of the euro locked exchange rates, leaving governments with only fiscal tools—like cutting spending or raising taxes—to manage economic shocks.

A Tale of Two Europes: North-South Imbalances

Over time, a significant economic divergence emerged within the eurozone. Northern economies, like Germany, maintained high competitiveness and accumulated large current account surpluses. In contrast, Southern economies ran chronic deficits, often financed by cheap credit flowing from the North.

Prolonged low interest rates set by the European Central Bank (ECB) encouraged massive borrowing in the South. This fueled unsustainable real estate booms, especially in Spain and Ireland, and led to a dangerous accumulation of both public and private debt.

Timeline of the Eurozone Debt Crisis History

The crisis didn’t erupt overnight. It was a chain reaction sparked by the global financial crisis of 2008 and ignited by revelations of hidden debt in Greece.

The Spark: Global Financial Crisis and Greek Revelations

The 2008 global financial crisis was the immediate precursor. It destabilized European banks, forcing many governments to issue guarantees or bail them out. This action transferred massive private debts onto public balance sheets, causing sovereign debt levels to swell.

The tipping point came in late 2009. The newly elected Greek government revealed that the country’s budget deficit was 15.4% of GDP—more than double the previously reported figure. This shocking disclosure shattered investor confidence in Greek bonds and sent its borrowing costs soaring.

Contagion and Bailouts (2010–2012)

Fear quickly spread from Greece to other heavily indebted nations. This “contagion” effect threatened the stability of the entire eurozone. The sequence of events was rapid:

- Late 2009: Greece discloses its hidden deficit, and its credit rating is downgraded.

- 2010–2011: Panic spreads to Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Italy—the so-called PIIGS countries. Fears of a sovereign default intensify.

- May 2010: The first international bailout for Greece is agreed upon, with the EU and International Monetary Fund (IMF) providing funds in exchange for strict austerity measures.

- 2010–2012: Ireland and Portugal receive their own bailouts. Spain requests a rescue package specifically for its banks, and Italy sees its borrowing costs rise to unsustainable levels.

“Whatever It Takes”: The ECB Steps In

By the summer of 2012, the crisis reached its peak. In a landmark speech, ECB President Mario Draghi promised to do “whatever it takes to preserve the euro.” This statement was backed by the announcement of the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program, a conditional but potentially unlimited bond-buying plan. The pledge successfully calmed markets and is widely seen as a turning point in the crisis.

The Epicenter: Understanding the P.I.I.G.S. Countries’ Debt

The acronym PIIGS refers to Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain, the five eurozone economies most severely impacted. While often grouped together, each nation faced a unique set of problems that led to its crisis.

- Greece: Fiscal mismanagement and unsustainable public spending.

- Ireland: A massive banking collapse following the burst of a property bubble.

- Spain: The collapse of a decade-long real estate boom, which crippled its banking sector.

- Portugal: Low competitiveness and persistent budget deficits.

- Italy: Chronically low economic growth combined with one of the world’s largest public debt piles.

A Closer Look: The Greek Debt Crisis Timeline

Greece was the epicenter of the crisis, enduring a painful and protracted ordeal that reshaped its economy and society. The country’s experience stands out as one of the most severe historical currency crises of the modern era. You can find a detailed account at the Council on Foreign Relations.

- October 2009: The new government reveals the true size of the national deficit, triggering the crisis.

- May 2010: Greece receives its first bailout package of €110 billion from the EU and IMF.

- 2012: Private-sector bondholders are forced to accept significant write-downs on their Greek debt.

- March 2012: A second, larger bailout of €130 billion is approved, accompanied by the largest sovereign debt restructuring in history.

- Following Years: The Greek economy contracts by over 25%, unemployment soars above 25%, and intense social unrest follows years of harsh austerity.

The Response: Policy Interventions and Their Consequences

The crisis forced European institutions to take unprecedented actions, fundamentally changing the architecture of the eurozone and the lives of its citizens.

The European Central Bank Role in the Crisis

Originally designed with a narrow mandate to control inflation, the European Central Bank (ECB) had to evolve rapidly. As private lending to indebted nations dried up, the ECB stepped into the void with several key interventions:

- Providing Liquidity: It offered cheap, long-term loans to struggling banks through its Long-Term Refinancing Operations (LTROs).

- Purchasing Government Bonds: It stabilized sovereign bond markets through the Securities Markets Programme (SMP) and later the OMT.

- Coordinating Bailouts: It worked alongside the EU and IMF (the “Troika”) to design and monitor the conditions of bailout programs.

The Human Cost of Austerity Measures in the Eurozone

In exchange for financial assistance, countries like Greece, Portugal, and Spain were required to implement severe austerity measures. These policies were designed to reduce budget deficits and restore market confidence but came at a staggering social cost. According to Encyclopædia Britannica, these measures included deep spending cuts, tax hikes, pension reductions, and labor market reforms.

The result was deep, prolonged recessions, skyrocketing unemployment, and a sharp increase in poverty and inequality. The harshness of these policies led to widespread social protests and fueled a contentious debate among economists over the effectiveness of prioritizing fiscal discipline over economic growth during a downturn.

Legacy and Lasting Reforms

The eurozone debt crisis left a profound legacy, forcing the European Union to build stronger institutional defenses to prevent a repeat disaster. The experience led to major reforms aimed at strengthening fiscal oversight and creating permanent crisis-management tools.

Key reforms include:

- The Fiscal Compact: A treaty that enshrined stricter budget rules into national law for member states.

- The European Stability Mechanism (ESM): A permanent bailout fund with the capacity to provide financial assistance to member states in distress.

- A Banking Union: A system to centralize the supervision and resolution of banks at the European level, increasing the ECB’s powers.

Despite these changes, debates continue about the future of the single currency, the need for greater risk-sharing among member states, and the social costs of the crisis management strategies employed.

Frequently Asked Questions

What caused the eurozone debt crisis?

The core causes included structural flaws in the eurozone’s design, fiscal mismanagement in some countries, the impact of the 2008 global financial crisis, and significant economic imbalances between Northern and Southern European economies.

What were the PIIGS countries and why did they struggle?

PIIGS stands for Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain. They were the countries most affected by the crisis, each for a different combination of reasons, including government overspending, banking collapses, uncompetitive economies, or burst real estate bubbles.

How did the European Central Bank intervene during the crisis?

The ECB provided emergency liquidity to banks, purchased government bonds to calm panicked markets, and ultimately pledged unlimited support to distressed countries that agreed to reforms, a promise that proved crucial in ending the acute phase of the crisis.

What were the consequences of austerity measures implemented in the eurozone?

Austerity measures led to deep recessions, soaring unemployment rates (exceeding 25% in Greece and Spain), cuts in public services, widespread social unrest, and rising poverty in the countries that received bailouts.

How did the Greek debt crisis unfold?

It began in late 2009 when Greece revealed hidden deficits. This led to a loss of market access, two massive international bailouts conditioned on harsh austerity, the largest debt restructuring in history, and a severe economic depression that lasted for years.

The eurozone debt crisis was a defining moment for the European Union, testing its solidarity and forcing it to evolve. The history of this period serves as a critical lesson in the complexities of monetary unions and the profound economic and social impact of sovereign debt. By understanding these events, we can better appreciate the ongoing challenges and reforms shaping Europe’s economic future and its place in the global financial system.