Keynes vs. White: The Competing Visions for Bretton Woods

In the summer of 1944, as World War II raged towards its conclusion, delegates from 44 Allied nations gathered in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. Their mission was monumental: to design a new global financial system that would prevent the economic chaos of the preceding decades. At the heart of this conference was a profound intellectual and political clash, a debate now known as the Keynes vs White Bretton Woods showdown, which pitted the visions of two brilliant economists against each other: John Maynard Keynes of the United Kingdom and Harry Dexter White of the United States.

This was more than an academic exercise; it was a battle to define the future of international trade, finance, and power. The outcome would shape the world economy for decades, creating institutions that remain central to global governance today. Understanding their competing proposals reveals the fundamental tensions between a war-depleted debtor nation and an ascendant creditor power, a conflict that still echoes in modern discussions of global economic imbalances.

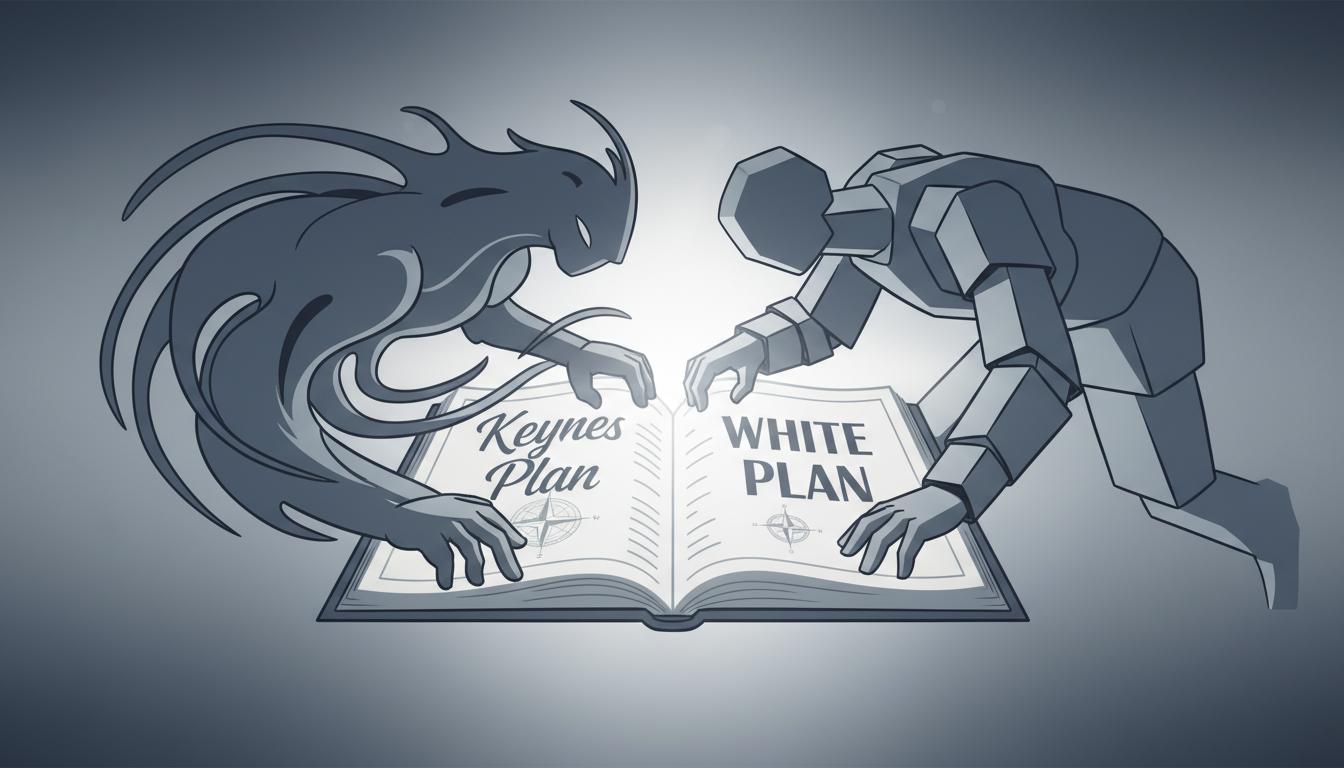

Keynes’s Ambitious Proposal: The International Clearing Union

Representing a Great Britain exhausted and indebted by war, John Maynard Keynes sought to create a system that promoted growth and flexibility. He drew lessons from the deflationary pressures of the 1920s and the breakdown of global trade. His solution was radical, expansive, and designed to avoid the pitfalls of the past.

The ‘Bancor’ and Symmetrical Adjustment

The centerpiece of the bancor proposal Keynes put forward was a new international currency, the bancor, which would be used exclusively for settling international accounts. This currency would be managed by a global institution called the International Clearing Union (ICU), effectively a world central bank.

Keynes’s system was designed with several key features:

- Massive Liquidity: The Clearing Union would be endowed with the ability to create new international reserves, offering overdraft facilities to deficit countries up to an estimated $26 billion. This was a substantial figure, considering the US GDP at the time was around $200 billion.

- Support for Debtors: The system was explicitly designed to help debtor nations, like the UK, avoid deflationary policies (cutting spending, raising taxes) to correct trade imbalances.

- Symmetrical Burden-Sharing: Crucially, Keynes insisted that both deficit and surplus countries had a responsibility to maintain equilibrium. Countries running persistent surpluses would be penalized, required to pay interest on their excess bancor holdings or remit them back to the ICU. This automatic mechanism was meant to discourage the hoarding of reserves and encourage balanced trade.

The Keynes Plan was a vision of mutual obligation, aiming to prevent both excessive deficits and surpluses from destabilizing the global economy.

White’s Pragmatic Plan: Stability and the US Dollar

Harry Dexter White, representing the United States, approached the problem from a completely different perspective. The US emerged from the war as the world’s undisputed economic powerhouse and primary creditor, holding the majority of global gold reserves. White’s goal was to create a stable, predictable system that would maintain price discipline and cement America’s central role.

The International Stabilization Fund (The White Plan IMF)

White’s proposal, which became the blueprint for the International Monetary Fund (IMF), was more conservative and controlled than Keynes’s grand vision. He worried that Keynes’s plan would create too much liquidity, potentially fueling inflation and channeling a flood of new money towards US exports, further concentrating reserves in American hands.

The core tenets of the White Plan IMF included:

- A Limited Resource Pool: Instead of a world central bank creating new money, White proposed a fund capitalized by member nations. This pool, initially set at $8.8 billion, would provide loans to countries facing temporary balance-of-payments difficulties.

- The Dollar-Gold Standard: The system would be anchored by the U.S. dollar, which itself was convertible to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce. Other currencies would be pegged to the dollar, creating a “gold exchange standard.”

- Conditional Lending: Unlike Keynes’s automatic overdrafts, access to the fund’s resources would come with conditions. The IMF would have oversight over a country’s exchange rate adjustments and economic policies, reflecting US interests in preventing reckless fiscal expansion by debtor nations.

Keynes vs White at Bretton Woods: The Core Disagreements

The opposing views at Bretton Woods stemmed from fundamentally different national interests and economic philosophies. While negotiations were often collegial, the power imbalance between the two nations was stark. The United States had the financial leverage, and its vision ultimately shaped the final agreement.

The key differences can be summarized as follows:

- Primary Goal: Keynes prioritized growth and flexibility, aiming to prevent deflation and unemployment. White prioritized stability and discipline, aiming to control inflation and maintain a fixed-rate system.

- Central Mechanism: Keynes proposed a Clearing Union that could create its own currency (bancor). White proposed a Stabilization Fund (the IMF) that worked with a pool of existing national currencies and gold.

- Adjustment Burden: Keynes advocated for symmetrical adjustment, placing pressure on both surplus and deficit countries. White’s plan placed the adjustment burden almost entirely on deficit countries.

- Scale: Keynes envisioned a system with $26 billion in liquidity. White’s was far smaller, with just $8.8 billion.

Ultimately, Britain’s desperate need for post-war funding from the United States forced its delegation to concede on most key points.

The Outcome and a Power-Imbalanced Compromise

The final Bretton Woods system was a compromise, but one that hewed much closer to White’s plan. It established the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, with the U.S. dollar at the undisputed center of the global financial order. The revolutionary idea of the bancor was discarded.

A unique insight from the conference highlights America’s dominant position. In the final hours, the agreement’s wording was subtly changed from pegging currencies to ‘gold’ to pegging them to ‘gold and U.S. dollars.’ As detailed by the Federal Reserve’s own historical accounts, this seemingly minor alteration officially cemented the dollar’s role as the world’s primary reserve currency.

While Keynes lost the main battle, he did win some concessions, such as a “scarce currency” clause that could theoretically put pressure on a nation running a massive surplus. However, the system created few automatic penalties for surplus nations, a point Keynes argued vehemently against.

The Enduring Legacy of the Keynes vs. White Debate

In the decades that followed, many of Keynes’s warnings proved prescient. The system’s asymmetry, which placed the burden of adjustment on deficit nations, contributed to currency crises and growing global imbalances. Historical reviews and expert analyses, including working papers from the IMF itself, often conclude that the points where Keynes was overruled became the system’s primary weaknesses.

The intellectual battle between Keynes and White was not just a historical event; it laid the foundation for ongoing debates in international economics. Discussions about global liquidity, the role of surplus nations like China and Germany, and proposals for reforming the international monetary system frequently revisit the ideas first championed by Keynes. His vision of a more balanced, symmetrical system remains a powerful and relevant concept for policymakers today.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the main difference between the Keynes Plan and the White Plan at Bretton Woods?

The Keynes Plan proposed a new international currency (bancor) and a global clearing union, while the White Plan favored a fund (IMF) using national currencies and gold, placing the US dollar at the center of the system.

Why did the US plan (White Plan) win over the British proposal at Bretton Woods?

The United States was the dominant postwar creditor with control over most global reserves; Britain’s acute need for US financial support led to acceptance of a compromise closer to White’s plan.

What was the ‘bancor’ proposed by Keynes?

The bancor was a theoretical supranational currency intended to facilitate international trade and settlements via an International Clearing Union, preventing persistent surpluses and deficits.

How did the outcome of Bretton Woods address (or fail to address) persistent surpluses and deficits?

The system placed most adjustment burdens on deficit countries; Keynes’s ideas for symmetrical penalties on surplus nations were not fully implemented, contributing to later imbalances.

Conclusion

The contest of ideas between John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White was a defining moment in modern economic history. It was a clash between a vision for expansive, managed globalization and one rooted in disciplined stability anchored by a dominant national power. While White’s plan provided the framework for the postwar economic boom, Keynes’s critiques highlighted structural flaws that would eventually contribute to the system’s demise.

The legacy of their debate endures, reminding us that the architecture of global finance is a product of both brilliant ideas and harsh political realities. This pivotal debate was just one chapter in the broader story of the Bretton Woods agreement, a system whose influence is still felt today.