The Maastricht Treaty 1992: The Foundation for the Single Currency

The creation of the European Union and its single currency, the euro, represents one of the most ambitious political and economic projects of the 20th century. This monumental shift did not happen overnight; it was the result of a landmark agreement that laid a precise foundation for European integration. The Maastricht Treaty euro connection is central to this story, as the 1992 treaty formally established the legal framework, economic criteria, and political will needed to turn the vision of a single currency into a reality.

Formally known as the Treaty on European Union, this agreement, signed in the Dutch city of Maastricht, went far beyond simple economic cooperation. It created the European Union as a unique political entity, introduced the concept of EU citizenship, and, most critically, outlined the strict roadmap for adopting the euro. For any nation wishing to join the monetary union, the path was clear: meet a series of tough economic targets designed to ensure stability and convergence.

From the EEC to the EU: A New Vision for Europe

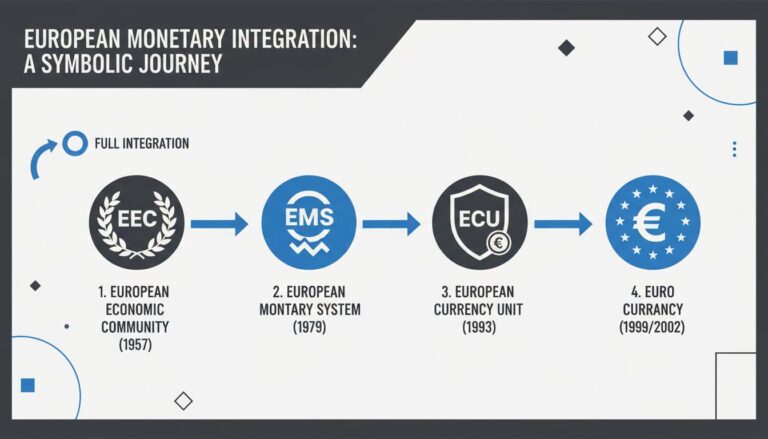

Before the Maastricht Treaty, European integration was largely driven by the European Economic Community (EEC), established by the Treaty of Rome in 1957. The EEC’s primary goal was economic: to create a common market, remove customs barriers, and foster mutual growth among member nations. For decades, this model proved successful in promoting peace and prosperity in post-war Europe.

By the late 1980s, however, European leaders felt a need for deeper integration. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War created a new geopolitical landscape. The European Economic Community history culminated in a push for a more profound union—one that addressed not only trade but also foreign policy, security, and justice. The Maastricht Treaty was the answer, transforming the economic community into a comprehensive political union.

This new structure was built on three “pillars”:

- The Community Pillar: This incorporated the existing EEC structures, covering economic, social, and environmental policies.

- Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP): This pillar aimed for coordinated external policies and joint action on the world stage.

- Justice and Home Affairs (JHA): This focused on cross-border cooperation in fighting crime, terrorism, and managing asylum and immigration.

Within this new framework, the plan for a single currency was the most ambitious and tangible step toward a more unified Europe.

The Economic Heart: The Maastricht Treaty Criteria for the Euro

To ensure the new single currency would be strong and stable, the treaty’s architects established a set of strict economic prerequisites. Known as the Maastricht Treaty criteria, or “convergence criteria,” these were non-negotiable hurdles that countries had to clear before they could abandon their national currencies and adopt the euro. The goal was to enforce fiscal and monetary discipline, preventing less stable economies from jeopardizing the entire currency union.

These five binding macroeconomic targets were designed to reassure economically cautious nations, particularly Germany, about the soundness of the project. Learn more about the history of Germany’s robust currency in our article on the Deutsche Mark.

The Maastricht criteria are:

- Inflation Rate: The national inflation rate could be no more than 1.5 percentage points higher than the average of the three best-performing (lowest inflation) member states.

- Government Budget Deficit: A country’s annual government deficit could not exceed 3% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

- Government Debt-to-GDP Ratio: The total national public debt could not be higher than 60% of GDP. If it was higher, it had to be sufficiently diminishing and approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace.

- Exchange Rate Stability: The country had to participate in the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) for at least two consecutive years without severe devaluations or tensions.

- Long-Term Interest Rates: Long-term interest rates could not be more than 2 percentage points higher than those of the three best-performing member states in terms of price stability.

These rules remain foundational to the Eurozone’s governance today and were instrumental in shaping the fiscal policies of member states in the run-up to the euro’s launch.

More Than Money: The Political Reasons for the Euro

While the economic rationale for the euro was clear—facilitating trade, eliminating exchange rate risk, and creating a massive single market—the political reasons for the euro were equally, if not more, powerful. The project was deeply intertwined with the historic events of the late 1980s and early 1990s, most notably the reunification of Germany.

Leaders across Europe, particularly in France, harbored concerns that a larger, reunified Germany could become an overly dominant economic and political force on the continent. The euro was seen as a way to bind Germany irrevocably into the European project. By ceding control of its powerful Deutsche Mark to a supranational institution, Germany would demonstrate its commitment to a shared European future, balancing its national interests within an integrated framework.

Furthermore, the macroeconomic instability of the 1970s, marked by high inflation and volatile currency fluctuations, spurred leaders to seek a more stable system. They envisioned a monetary union that would shield economic policy from short-term political pressures, fostering long-term stability and growth. This shared commitment formed the political backbone of the Maastricht Treaty’s monetary ambitions.

A New Era of Monetary Policy in Maastricht

The treaty fundamentally altered the landscape of European finance by centralizing monetary authority. The provisions for the monetary policy in Maastricht called for the creation of a new, independent institution to manage the single currency and ensure price stability. This institution would become the European Central Bank (ECB).

Once a country adopted the euro, its national central bank would transfer its authority over monetary policy—such as setting interest rates and managing currency supply—to the ECB. This marked the end of “monetary nationalism” for participating members. Governments could no longer devalue their currencies to gain a competitive edge or print money to finance deficits. As outlined by the Encyclopædia Britannica, this shift was a profound transfer of national sovereignty to a supranational level, intended to create a unified and resilient economic bloc.

Legacy of Maastricht: A Foundation Under Pressure

The ratification of the Maastricht Treaty was not without its challenges. It faced political crises, narrow referendum victories, and heated debates between federalists and those fiercely protective of national sovereignty. Despite the controversy, the treaty entered into force in 1993, and its vision has largely been realized. Today, 20 of the 27 EU member states use the euro.

The treaty’s legacy, however, is complex. The strict fiscal rules—the Maastricht criteria—were put to the ultimate test during the Eurozone debt crisis that began in 2009. The crisis exposed both the strengths and weaknesses of the original framework, revealing how difficult it can be to enforce fiscal discipline across diverse economies without a corresponding political union. According to the official EU Council website, the treaty remains a foundational text for the Union’s operations.

Decades later, the Maastricht Treaty stands as a pivotal moment in modern history. It created the institutional and economic architecture for today’s European Union and provided the blueprint that made the euro possible.

Frequently Asked Questions

What were the main goals of the Maastricht Treaty?

The main goals of the Maastricht Treaty were to officially create the European Union as a political entity, establish a single market, introduce EU citizenship, and lay the detailed groundwork for a single European currency, the euro. It also aimed to deepen cooperation in foreign policy, security, and justice.

What are the Maastricht convergence criteria for adopting the euro?

The five criteria are: a low inflation rate (no more than 1.5% above the three best performers), an annual government deficit below 3% of GDP, a public debt-to-GDP ratio below 60% or sufficiently diminishing and approaching the reference value, stable exchange rates within the ERM for two years, and low long-term interest rates (no more than 2% above the three best performers).

Why did European leaders want a single currency like the euro?

The euro was created to foster economic stability, simplify cross-border trade, and eliminate currency exchange risks. Politically, it was a powerful tool to bind EU countries closer together and anchor a reunified Germany firmly within the European project, preventing any single nation from becoming too dominant.

Conclusion

The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 was more than just an agreement; it was a bold declaration of a new European future. By establishing the European Union and meticulously defining the economic rules for monetary union, it provided the essential foundation for the euro. The treaty masterfully balanced ambitious political goals with pragmatic economic requirements, creating a framework that continues to shape the continent today.

From the strict convergence criteria to the establishment of a centralized monetary policy, the treaty’s provisions were instrumental in the creation of the euro. While its legacy has been tested by economic crises, its role as the blueprint for Europe’s single currency is undeniable, marking a defining moment in the long history of European integration.