Hyperinflation Examples: Zimbabwe, Weimar Republic, and Hungary’s Pengő

When the price of goods spirals out of control so fast that money becomes virtually worthless, an economy enters a state of hyperinflation. This isn’t just high inflation; it’s an economic whirlwind that can wipe out savings in days and force citizens to carry cash in wheelbarrows. Examining key hyperinflation history examples reveals a chilling pattern of monetary collapse driven by lost confidence and reckless government policy.

Defined by economists as an inflation rate exceeding 50% per month, hyperinflation destroys a currency’s value, shatters public trust, and cripples economic activity. The stories of the Weimar Republic, Hungary, and modern Zimbabwe serve as stark warnings, each offering crucial insights into how a nation’s money can lose all meaning.

Weimar Republic Hyperinflation Causes and Collapse (1921–1923)

Post-World War I Germany provides one of history’s most studied cases of hyperinflation. The Weimar Republic’s economic crisis was a perfect storm of war debt, crippling reparations payments, and a fundamental collapse in public trust.

The Road to Ruin: Reparations and Money Printing

Saddled with immense war reparations dictated by the Treaty of Versailles, the German government found itself unable to pay its bills through taxation. Instead, it resorted to printing massive quantities of the papiermark to cover its deficits. This decision ignited a vicious cycle: the more money it printed, the less valuable the currency became, prompting even more aggressive printing.

This spiral sent prices soaring at an uncontrollable rate. By November 1923, the German mark was practically worthless, with an exchange rate reaching over 4.2 trillion marks to one US dollar. The currency had lost its function as a store of value, forcing a return to barter for everyday transactions.

Societal Impact and Lasting Scars

The consequences were devastating for German society. The crisis wiped out the savings of the middle class, impoverished millions, and fueled deep social and political unrest. This economic instability is often cited as a key factor that contributed to the volatile political climate of the era. The complete breakdown of the monetary system underscores the profound connection between economic stability and social order, a topic explored further in the causes of the Papiermark’s hyperinflation.

The Hungarian Pengő Record: The Worst Hyperinflation in History (1945–1946)

While the Weimar Republic is famous, the post-World War II hyperinflation of the Hungarian pengő holds the undisputed world record for the most extreme monetary collapse ever recorded. The sheer scale of the crisis is almost beyond comprehension.

A Post-War Economic Catastrophe

Emerging from the devastation of World War II with its industrial and agricultural base in ruins, Hungary faced an impossible economic situation. The government, lacking a tax base, printed money to fund its operations, triggering a catastrophic loss of confidence in the pengő.

At its peak in July 1946, prices were doubling approximately every 15 hours. The monthly inflation rate reached an astronomical 41.9 quadrillion percent. The government was forced to issue increasingly absurd denominations, culminating in the 100 quintillion (100,000,000,000,000,000,000) pengő note, the highest denomination banknote ever issued.

The Aftermath and the Forint

The pengő became utterly worthless. In August 1946, Hungary introduced a new currency, the forint, to restore stability. The conversion rate illustrates the severity of the crisis: one new forint was exchanged for 400 octillion (4 x 1029) pengő, effectively erasing the old currency from existence.

A Modern Case Study: Zimbabwe Hyperinflation Facts (2000s)

One of the most severe and recent hyperinflation history examples occurred in Zimbabwe during the 2000s. This episode demonstrates that the economic forces driving hyperinflation are not confined to the post-war turmoil of the 20th century.

Triggers of the Collapse

Zimbabwe’s crisis was rooted in a combination of factors that dismantled its once-productive economy. Key drivers included:

- Disruptive Land Reforms: Policies in the early 2000s led to a sharp fall in agricultural output, a cornerstone of the nation’s economy.

- Economic Mismanagement: Widespread corruption and unsustainable government spending created massive budget deficits.

- Aggressive Money Printing: To finance these deficits, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe began printing money on an enormous scale.

- Loss of Confidence: As the currency’s value plummeted, public and investor trust in the government and its policies evaporated.

Peak Inflation and Societal Breakdown

By November 2008, Zimbabwe’s monthly inflation rate peaked at an estimated 79.6 billion percent. The government issued notes in ever-higher denominations, including the now-infamous 100 Trillion Zimbabwean Dollar bill. Prices for basic goods like bread and milk would change multiple times a day.

The consequences were catastrophic. Banking and credit systems collapsed, savings were erased, and citizens resorted to using foreign currencies like the U.S. dollar or bartering for essential goods. In 2009, the government was forced to officially abandon the Zimbabwean dollar, a move that highlighted how technical fixes like revaluing the currency fail without fundamental institutional and fiscal reforms.

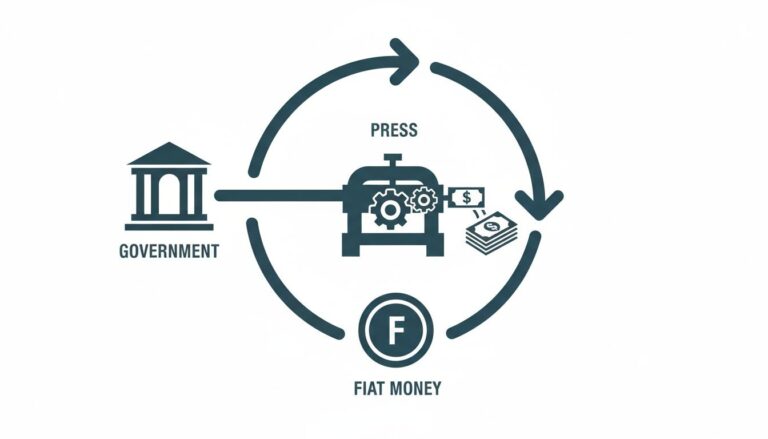

What Causes Fiat Currency Hyperinflation? Common Triggers

These historical episodes, though separated by time and geography, share a common set of triggers. Understanding these factors is crucial to grasping the nature of hyperinflation in economies based on modern fiat currency.

The primary causes almost always include:

- Sustained Government Budget Deficits: When a government consistently spends far more than it collects in taxes and cannot borrow, it may resort to printing money to pay its bills.

- Collapse in Production: A severe drop in economic output, whether from war, mismanagement, or political upheaval, means there are fewer goods and services for money to chase.

- Loss of Public Confidence: This is the crucial accelerator. Once people expect prices to rise rapidly, they rush to spend their money, pushing prices up even faster in a self-fulfilling prophecy.

- Political Instability: War, revolution, or institutional collapse often precede hyperinflation, as they destroy productive capacity and undermine faith in the government’s ability to manage the economy.

Failed government policies, such as price controls, often make the situation worse by creating shortages and driving economic activity into black markets. As noted by economists at the Cato Institute, once inflationary expectations take hold, reversing them requires drastic and credible structural reforms.

Key Lessons from Historical Currency Crises

The study of hyperinflation offers clear and enduring lessons about monetary stability. The most critical insight is that public trust is the bedrock of any functional currency. In every case, trust in the government and its institutions collapsed before the money became worthless.

Furthermore, these events show that recovery is a long and arduous process that requires more than just introducing a new currency. It demands restoring fiscal discipline, rebuilding productive capacity, and re-establishing trust in governance. These historical currency crises serve as a powerful reminder of the dangers of uncontrolled government spending and the importance of independent, disciplined monetary policy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the definition of hyperinflation?

Economists typically define hyperinflation as a period when the monthly inflation rate exceeds 50%. This rapid and out-of-control price increase quickly erodes the real value of a local currency and can render it worthless.

What caused Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation?

Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation in the 2000s was primarily caused by the government printing excessive amounts of money to fund its deficits. This was compounded by a severe decline in agricultural and industrial output following controversial land reforms, widespread corruption, and a total collapse of public trust in the currency and government.

How does Hungary’s hyperinflation compare globally?

Hungary’s 1946 hyperinflation of the pengő is the most severe case ever recorded in world history. At its peak, prices doubled every 15 hours, and the monthly inflation rate reached an estimated 41.9 quadrillion percent, making the currency completely valueless.

What are the main consequences of hyperinflation?

The consequences include the complete destruction of public savings, the collapse of banking and financial systems, and widespread poverty. Economic activity often grinds to a halt or reverts to bartering, and citizens are forced to use more stable foreign currencies for transactions, leading to a long-term loss of institutional trust.

Conclusion

The hyperinflation examples of the Weimar Republic, Hungary, and Zimbabwe are more than just historical footnotes; they are cautionary tales about the fragility of fiat currency. They reveal that when governments abandon fiscal discipline and public trust evaporates, the economic consequences can be swift and devastating. These events underscore the vital importance of sound economic policies and credible institutions in maintaining a stable and functional society.