Gold Convertibility: What It Meant for Paper Currency

Imagine holding a dollar bill that wasn’t just a piece of paper, but a direct promise—a claim check for a specific amount of physical gold stored in a vault. For much of modern history, this was the reality of money. This system, known as gold convertibility explained, was the bedrock of global finance, providing a tangible anchor to the value of currency and instilling confidence in paper money.

Gold convertibility is the principle that a country’s currency can be exchanged for a fixed quantity of gold. This direct link meant governments and banks couldn’t simply print more money at will; their issuance of currency was constrained by the amount of gold they held in their reserves. This fundamental concept shaped international trade, government spending, and the very trust people had in their money for much of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

What is Gold Convertibility? The Core Mechanism

At its heart, gold convertibility was a simple but powerful promise. It meant that paper currency was not just fiat money—valued only by government decree—but was instead a representative of a real, physical asset. This mechanism was the engine of the historical gold standard, which dominated the global economy from the late 19th to the mid-20th century.

The core components of this system were:

- Fixed Rate of Exchange: A government would publicly declare a fixed price for gold in its own currency. For example, the U.S. might set the price at $20.67 per troy ounce of gold, meaning you could exchange one ounce of gold for $20.67, or vice versa.

- Redeemable Currency: The paper money in circulation was considered currency redeemable in gold. This meant any individual, business, or even another country’s central bank could, in theory, take their paper notes to a bank and demand the equivalent value in gold coins or bullion.

- Reserve Backing: To maintain this promise, a country’s central bank had to hold sufficient gold reserves to back the currency it had issued. This created an automatic limit on how much money could be in circulation, directly tying the money supply to a physical commodity.

Gold Certificate History: Paper Money Backed by Gold

One of the most direct examples of gold convertibility in action was the issuance of gold certificates. In the United States, these special notes circulated from 1882 to 1933. Unlike regular currency, a gold certificate explicitly stated that a certain amount of gold coin or bullion was on deposit with the U.S. Treasury, payable to the bearer on demand.

This system of paper money backed by gold built immense public trust. People accepted paper notes for transactions because they knew each note was a guaranteed claim on a tangible asset with intrinsic value. This confidence was crucial for the growth of commerce and banking during that era.

The Evolution of Convertibility Through History

Gold convertibility wasn’t a static concept; it evolved significantly over time, adapting to economic and political pressures. Its application varied across different historical periods, each with its own set of rules.

The Classical Gold Standard (c. 1870s–1914)

This period is considered the heyday of gold convertibility. Major economies, led by Great Britain, tied their currencies to gold at a fixed rate. Under this “gold specie standard,” currency was freely convertible into gold, and gold coins often circulated alongside paper notes. Central banks had one primary duty: maintain this convertibility and defend the fixed exchange rate. This system collapsed with the outbreak of World War I, as nations suspended gold exports to finance their war efforts.

The Interwar Period and Bretton Woods (1918–1971)

After World War I, attempts to restore the classical gold standard largely failed, succumbing to the economic turmoil of the Great Depression. A new system emerged from the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement, creating a “gold exchange standard.”

Under this new arrangement:

- Only the U.S. dollar was directly convertible to gold, and only for foreign governments and central banks, not for individuals. The price was fixed at $35 per ounce.

- All other major currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar at a fixed exchange rate. This made the dollar the world’s primary reserve currency.

This system provided decades of relative economic stability but put immense pressure on the United States to maintain its gold reserves as the global economy grew.

The Advantages of Gold Convertibility Explained

For as long as it lasted, a system based on gold convertibility offered several key benefits that many economists and policymakers found attractive. These advantages created a predictable and stable international financial environment.

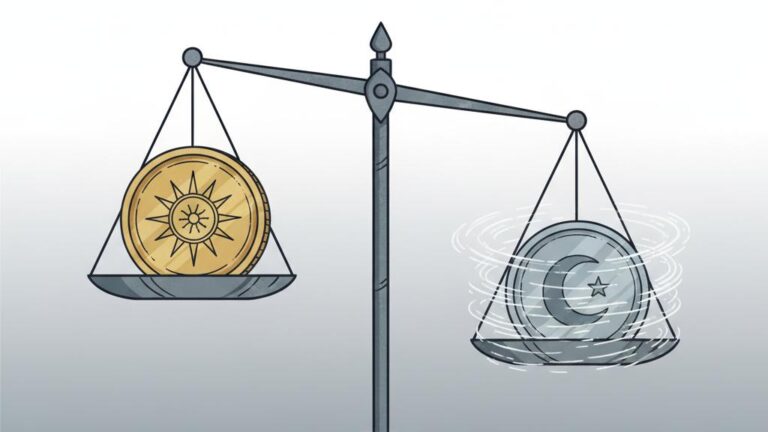

- Currency Stability and Inflation Control: Because the money supply was tied to a physical supply of gold, governments could not easily inflate their currency by printing excessive amounts. This enforced strict limits on monetary expansion, helping to keep inflation low and predictable.

- Fixed Exchange Rates: With each currency pegged to gold, the exchange rates between countries were effectively fixed. This eliminated currency risk, which greatly encouraged and simplified international trade and investment.

- Fiscal and Monetary Discipline: Gold convertibility acted as a “straitjacket” on politicians and central bankers. If a government engaged in excessive deficit spending, it could lead to an outflow of gold as confidence waned, forcing a reversal of policy. As explained by the Library of Economics and Liberty, this discipline was a core feature of the system.

The End of an Era: Why Nations Abandoned Gold Convertibility

Despite its advantages, the gold standard’s rigidity ultimately became its downfall. The system struggled to cope with major economic shocks like wars and deep recessions. During the Great Depression, countries were forced to abandon gold convertibility to gain the flexibility needed to stimulate their economies.

The final nail in the coffin came on August 15, 1971. Facing dwindling gold reserves and mounting economic pressures, U.S. President Richard Nixon announced he was “closing the gold window.” This act, detailed by the Federal Reserve History, suspended the U.S. dollar’s convertibility into gold for foreign governments, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system.

This pivotal moment, often called the Nixon Shock, severed the last formal link between the world’s major currencies and gold. It ushered in the modern era of fiat currencies, where money’s value is based solely on trust in the government that issues it, rather than on a physical commodity.

Legacy and Modern Perspective

Today, no major country uses gold convertibility. All global economies operate on a fiat money system. However, gold has not disappeared from the financial world; central banks still hold it as a significant reserve asset due to its historic role as a store of value.

The debate over the merits of gold-backed versus fiat currency continues. Proponents of a return to gold argue it would instill discipline and prevent inflation, while opponents claim it is too rigid for a complex, modern global economy. While the era of gold convertibility is over, its legacy continues to influence discussions about monetary policy, inflation, and the fundamental nature of money.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the gold standard and how did it work?

The gold standard was a monetary system where a country’s currency was directly tied to a specific quantity of gold. This allowed paper money to be exchanged for a fixed amount of gold held in reserve by the central bank, ensuring the currency’s value was backed by a physical asset.

What were gold certificates and were they truly redeemable?

Gold certificates were a form of paper currency, used primarily in the U.S. from 1882 to 1933, that explicitly promised the bearer could exchange them at a bank for a specified amount of gold coinage or bullion. They were truly redeemable until the U.S. government ended private gold ownership in 1933.

Why did countries abandon gold convertibility?

Countries abandoned gold convertibility primarily due to major economic crises like the Great Depression and World Wars. The system was too inflexible to allow governments the monetary policy freedom needed to combat recessions or finance large-scale efforts. The final break occurred in 1971 when the U.S. ended the dollar’s convertibility to gold.

Does any country use gold convertibility today?

No, no major country today uses gold convertibility. All major economies operate on fiat money systems, where the currency’s value is not backed by a physical commodity like gold but by government decree and public trust.

Understanding gold convertibility offers a crucial window into how our modern financial world was built. It highlights the long historical journey from money as a physical object to the abstract, trust-based fiat systems we use today. To learn more about this transformative period, explore our complete guide to the history and collapse of the gold standard.