The Bimetallic Standard: Why Gold and Silver Coinage Failed

For centuries, the idea of a currency backed by not one, but two precious metals—gold and silver—seemed like the ultimate solution for economic stability. This system, known as the bimetallic standard, promised the best of both worlds: the trusted value of gold and the widespread availability of silver. Yet, despite being adopted by major economies, including the United States, it ultimately failed.

The bimetallic standard history is a fascinating story of economic theory colliding with market reality. At its core, bimetallism was a monetary system where a nation’s currency was defined by fixed quantities of both gold and silver, with both metals serving as legal tender. But a simple economic principle, combined with shifting global supplies and political battles, unraveled this complex system, paving the way for the dominance of the gold standard.

What Was the Bimetallic Standard?

The bimetallic standard was a monetary system where the value of a country’s currency was legally fixed to specific amounts of both gold and silver. This meant that coins made from both metals circulated simultaneously and could be used to pay all debts, public and private. The government would guarantee a fixed exchange ratio between the two.

The system operated on three key principles:

- A Fixed Gold-to-Silver Ratio: The government set a legal, or “mint,” ratio for the value of gold to silver. For example, the U.S. Coinage Act of 1792 established a ratio of 15:1, meaning one ounce of gold was legally worth fifteen ounces of silver.

- Free Coinage: Citizens could bring either gold or silver bullion to the national mint and have it coined into money at the fixed ratio, usually for a small fee. This policy was meant to ensure the money supply could expand based on the availability of both metals.

- Legal Tender Status: Both gold and silver coins were accepted as legal payment for any transaction, from paying taxes to settling private debts.

In theory, bimetallism offered greater monetary flexibility and larger reserves than a system based on just one metal. By using both gold and silver, a nation could create a larger and more stable money supply. However, this delicate balance would prove almost impossible to maintain.

A Brief Bimetallic Standard History

While gold and silver coins had circulated together for centuries, the formalization of bimetallism occurred in the 18th and 19th centuries as nations sought to standardize their currencies. The system’s history is marked by ambitious legislation, attempts at international cooperation, and ultimately, widespread abandonment.

The United States Adopts Bimetallism

Following its independence, the United States established its monetary system with the Coinage Act of 1792. This landmark legislation, championed by Alexander Hamilton, officially placed the young nation on a bimetallic standard with the aforementioned 15:1 ratio. The goal was to create a reliable and abundant currency to fuel economic growth.

However, the government’s fixed ratio quickly ran into trouble. The market value of precious metals constantly fluctuates based on new discoveries and global demand. When the market ratio diverged from the mint’s legal ratio, one metal would inevitably become overvalued, leading to the problems predicted by Gresham’s Law.

Europe’s Experiment: The Latin Monetary Union

In Europe, France had long been a proponent of bimetallism. In 1865, it led the formation of the Latin Monetary Union (LMU), which included Belgium, Italy, and Switzerland. The LMU was an ambitious attempt to create an international bimetallic system by standardizing the weight and purity of gold and silver coins across member nations.

Despite its initial promise, the LMU faced constant challenges. Fluctuations in the global price of silver and the disruptions of events like the Franco-Prussian War put immense strain on the union. Member nations struggled to maintain the agreed-upon ratio, and the LMU eventually dissolved in the early 20th century, a clear signal that international bimetallism was unworkable.

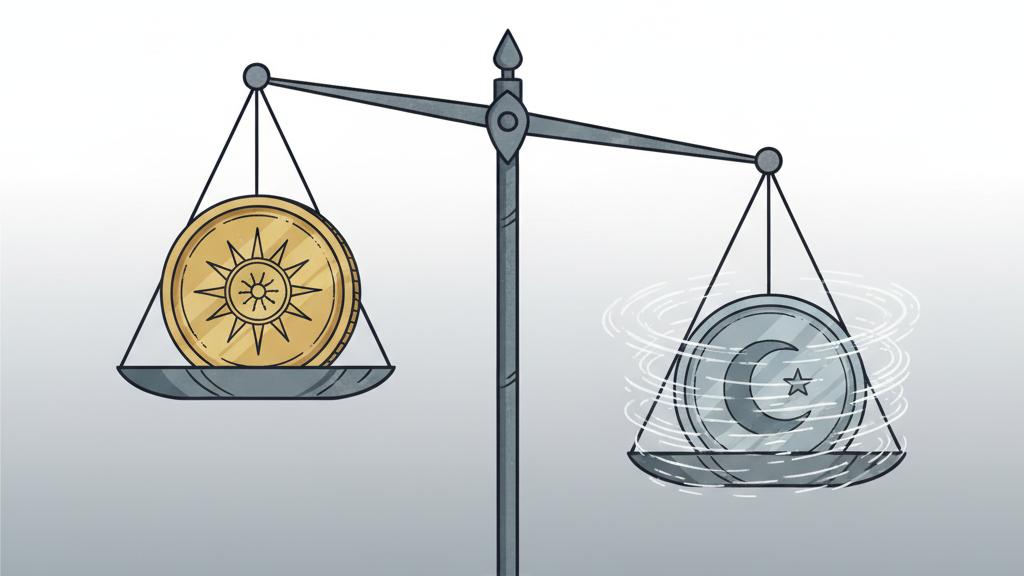

Silver Standard vs. Gold Standard: The Core Conflict

By the late 19th century, nations faced a critical choice between three competing monetary systems. The debate over the silver standard vs. gold standard pitted powerful economic and social interests against each other, with bimetallism caught in the middle.

| System | Definition | Key Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Standard | Currency value is fixed to a specific amount of gold alone. | Considered stable and fostered international trust. Favored by creditors and industrial interests. | Limited monetary flexibility, which could lead to deflationary pressures. |

| Silver Standard | Currency value is fixed to a specific amount of silver alone. | Simpler to manage in silver-rich economies like Mexico or China. | Vulnerable to silver price volatility and the global shift toward gold. |

| Bimetallic Standard | Currency value is fixed to both gold and silver at a set ratio. | Offered larger monetary reserves and potential price stability. | Susceptible to Gresham’s Law, complex to manage, and prone to breaking down. |

Ultimately, most major economies, including those in the Latin Monetary Union, began shifting toward the perceived stability of the gold standard. This trend isolated proponents of bimetallism and silver, setting the stage for one of the most intense political battles in U.S. history.

The “Free Coinage of Silver” Movement in America

In the United States, the move away from bimetallism began with the Coinage Act of 1873. This law ended the free coinage of silver, effectively placing the U.S. on a de facto gold standard. Supporters of silver quickly labeled the act the “Crime of ’73,” arguing it was a conspiracy by bankers and creditors to limit the money supply.

The issue was intensified by post-Civil War deflation. As prices fell, the real burden of debt for farmers and workers increased. These groups formed the backbone of the Populist movement and rallied around a powerful call for the free coinage of silver.

Their argument was simple: reintroducing unlimited silver coinage would expand the money supply, leading to inflation. This inflation would raise crop prices and make it easier for them to pay off their debts. This movement led to compromise legislation like:

- The Bland-Allison Act (1878): Required the U.S. Treasury to purchase a certain amount of silver each month and mint it into coins.

- The Sherman Silver Purchase Act (1890): Substantially increased the amount of silver the government was required to purchase.

The debate reached its zenith during the 1896 presidential election. Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan delivered his famous “Cross of Gold” speech, passionately advocating for bimetallism and free silver. Despite his powerful rhetoric, the political tide had turned, and the U.S. officially adopted the gold standard with the Gold Standard Act of 1900.

Gresham’s Law and Bimetallism: The Inevitable Failure

The fundamental reason for bimetallism’s failure can be explained by a centuries-old economic principle: Gresham’s Law. As defined by Britannica, the law states that “bad money drives out good.”

In the context of Gresham’s Law bimetallism, this worked as follows:

- The government sets a fixed mint ratio (e.g., 15 ounces of silver = 1 ounce of gold).

- The global market ratio changes due to supply and demand (e.g., 16 ounces of silver = 1 ounce of gold).

- At the mint, gold is now undervalued (you can get more silver for it on the open market), and silver is overvalued.

- “Good money” (undervalued gold) disappears from circulation as people hoard it or export it to sell at its higher market price.

- “Bad money” (overvalued silver) floods the economy because people rush to use it for payments while it’s worth more than its market value.

This process repeatedly turned bimetallic systems into de facto monometallic ones. The constant arbitrage between the mint and market ratios created instability, defeating the very purpose of the system. Without perfect international coordination to maintain a global ratio—an impossible task—bimetallism was doomed.

Conclusion: The Legacy of a Flawed System

By the dawn of the 20th century, the bimetallic standard was virtually extinct. Its history reveals a persistent tension between the desire for monetary flexibility and the need for economic stability. While it aimed to create a robust and adaptive currency system by leveraging both gold and silver, it couldn’t overcome the relentless logic of market forces.

The story of bimetallism serves as a powerful lesson in monetary policy, demonstrating the immense difficulty of fixing the price of one commodity in terms of another. Its failure led the world to embrace a single anchor for value, a system that would become known as the classical gold standard, which itself would face its own set of challenges in the century to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the bimetallic standard?

The bimetallic standard is a monetary system where a nation’s currency value is defined by specific amounts of both gold and silver. Both metals act as legal tender at a fixed, government-set ratio.

Why did bimetallism ultimately fail?

Bimetallism failed primarily due to the difficulty of maintaining a fixed gold-to-silver ratio that matched fluctuating market values. This discrepancy led to the effects of Gresham’s Law, where one metal would disappear from circulation, destabilizing the entire system.

What was the “free coinage of silver” movement?

It was a major political movement in the late 19th-century United States that advocated for the unlimited minting of silver coins. Its supporters, mainly indebted farmers, hoped to expand the money supply and cause inflation to relieve their debt burdens.

How did Gresham’s Law affect bimetallism?

Gresham’s Law (“bad money drives out good”) caused the metal that was overvalued at the mint’s fixed ratio to flood the economy, while the undervalued metal was hoarded or exported. This effectively turned the bimetallic system into a monometallic one, defeating its purpose.

When did the United States abandon the bimetallic standard?

The U.S. effectively abandoned bimetallism with the Coinage Act of 1873, which demonetized silver. It officially and fully committed to the gold standard with the Gold Standard Act of 1900.